Original Article - (2021) Volume 16, Issue 3

Received: 12-Apr-2021 Published: 28-Sep-2021

Background: Cesarean delivery (CD) rates have increased during the last few decades, and it has become the most common surgery during women’s reproductive years. The optimal choice of skin closure at cesarean delivery has not yet been determined. The aim of this study is to compare between two different materials used for skin closure at cesarean delivery; glue (Dermabond®; Ethicon, Somerville, NJ) and running subcuticular suture technique using monofilament (Monocryl®; Ethicon). Cosmetic appearance, wound complications and scar healing following cesarean delivery were evaluated.

Patients and methods: Seventy-nine patients undergoing cesarean section under spinal anesthesia were randomized into two groups to receive either Dermabond® glue (2-octyl-cyanoacrylate) or Monocryl® sutures after obtaining informed consent. All patients scheduled for an elective CD for various indications who agreed to participate in the study were included and provided signed informed consent. Postoperatively, the appearance of the scars was evaluated after one week as primary outcome, then they were re-evaluated one month and 6-month later after the CD. The evaluation was made by both the patient and the physician according to a validated scale which is the Patient and Observer Scar Assessment Scale (POSAS). In addition to that, surgical site infection was evaluated using Southampton wound scoring system along with Surgeons’ satisfaction using Surgeons’ satisfaction scale. Other post-operative complications as wound disruption, wound dehiscence (hematoma or seroma) and/or allergy to the material used was also assessed.

Results: The POSAS observer scale was assessed one week after the procedure and despite that there was significant difference between the two groups favoring the glue group at two items of assessment which were the vascularity and thickness with P-value of 0.000 and 0.006 respectively, there was no significant difference between the two groups regarding the overall opinion with P-value of 0.233. Regarding the POSAS patient scale, there was significant difference between the two groups favoring the glue group regarding two items of the assessment scale which are the pain and itching with P-value of 0.000 and 0.007, respectively; however, there was no significant difference between the two groups regarding the overall opinion with P-value of 0.110. There was no statistically significant difference between two groups regarding pre-operative and post-operative hemoglobin with P-value 0.417 and 0.689, respectively. There was highly statistically significant difference in case group than control group regarding the Surgeons’ satisfaction scale with P-value 0.000, the operating time with the material used with P-value 0.000 and the satisfaction with the final closure appearance with P-value 0.000. However, there was no statistically significant difference in the surgical site infection with P-value 0.378. The duration of closure of the skin was with highly significant difference in case group with P-value 0.000. However, there was highly statistically significant difference regarding the cost favoring control group with P-value 0.000.

Conclusion: The Dermabond® glue is relatively an effective, comfortable, and easy method of skin closure after cesarean delivery with low risk for surgical site infection. However, it is not cost effective.

Trial registration: Clinicaltrial.gov Registration number: NCT04371549

Cesarean delivery; Dermabond; POSAS; Surgical site infection

Cesarean delivery (CD) is one of the most performed surgeries worldwide [1]. The Cesarean delivery requires a relatively long skin incision, and efficient healing of the cesarean wound is a particularly important determinant of the postoperative satisfaction of the patient [2].

Suture closure is a safe and effective method, but time consuming and operator dependent, and there is a risk of needle stick injury [3]. Dermabond® glue (Ethicon Inc, Somerville, NJ) is a liquid monomer that forms a strong tissue bond with a protective barrier that adds strength and inhibits bacteria. An in vitro study found that glue inhibits both gram-positive (methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus and Staphylococcus epidermidis) and gram-negative (Escherichia coli) bacteria [4].

In addition, glue has the potential advantages of rapid application and repair time. It has been shown to achieve cosmetically similar results compared to staples within 12 months of the repair. Also, glue was shown to be well-accepted by patients [5]. Because of these advantages, Dermabond is now used for skin closure in various surgeries, but its use in cesarean skin wounds is not yet common and a few studies have assessed the feasibility of using a tissue adhesive for skin closure of cesarean transverse incisions [6].

This was a randomized, double-blinded controlled clinical trial which was conducted during the period from August 2020 to the end of March 2021. After obtaining informed consent, eighty pregnant women between 20 and 40 years of age who were scheduled for elective cesarean section were included in the study and were divided into two groups to have their skin closed after cesarean delivery by either Dermabond® glue (2-octyl-cyanoacrylate) (Group A) or continuous subcuticular suture by Monocryl® (poly(glycolide-co-l(−)-lactide)) (Group B). Patients who were scheduled for elective cesarean section (Category 4 CS) at term (≥ 37 weeks) with BMI 18.5 – 29.9 kg/m2, and hemoglobin level ≥ 10 gm/dl were included in our study. Major systemic medical disorder, allergy to the material used, previous cesarean delivery not using Pfannenstiel incision, abnormal placental invasion or uterine anomalies, history of surgical site infection and/or clinical signs of infection at time of cesarean delivery were the exclusion criteria. All the procedures were performed under spinal anesthesia.

Dermabond® (2-octyl-cyanoacrylate) is surgical glue that is FDA approved for use on humans. It comes in sterile, single-use applicators and is the glue of choice for surgeons closing incisions after an operation. Dermabond® is sterile, nontoxic, produces truly little heat as it cures, remains flexible after hardening, hardens in about 30 seconds, and is as strong as 5-0 stitches. To be labeled as sterile for medical use it is sold in 0.7 mL (0.02 oz), single-use applicators. A glass seal was broken before using each applicator, and if any glue left inside would be hardened, becoming unusable. In the glue group, we may need to use 2 layers of Dermabond® to close the outer skin layer. Based on manufacturer’s recommendations, the first layer of glue was applied to attach the skin edges. Sixty seconds later, a second layer may be added to improve the strength of the adhesion and to create a barrier intended to decrease wound infections. In group B, the skin was closed by running subcuticular suture technique using synthetic absorbable monofilament (Monocryl® 2-0).

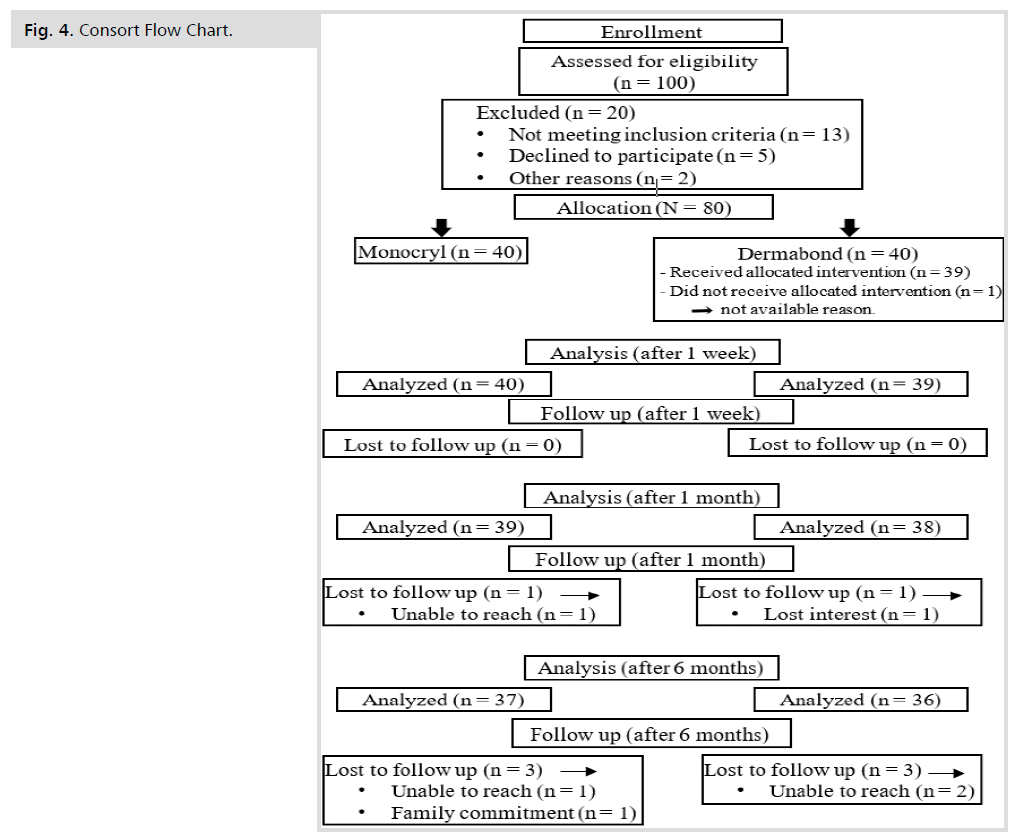

The 80 patients who were included in our study were randomized through a computer-generated system into 2 groups: group A (Dermabond glue) and group B (Monocryl). Each group included 40 patients with one patient in group A (glue) did not receive the allocated intervention due to hardening of the glue becoming unusable while group B. Allocation and concealment were done by sequentially sealed opaque envelopes. 80 envelopes were numbered serially from 1 to 80, 40 envelopes contained the letter A and the other 40 contained the letter B. To ensure that every patient fulfilling the inclusion criteria had the same chance of participating in this study, randomization was guided by a table of random members by a computer-based program (using www.randomization.com). When the first patient arrived, the patient was allocated according to the randomization table and so on. Ethical approval of this study was granted by the Research Ethics committee at the faculty of medicine, Ain Shams University, Egypt.

Regarding wound care, group A (glue group) was instructed not to use triple antibiotic ointment (Neosporin®) on the wound, as triple antibiotic ointment is petroleum based and causes it to dissolve. Also, Dermabond® can be dissolved in minutes using triple antibiotic ointment or other petroleum-based products. Moreover, they were instructed to keep the glued area dry while the incision is healing (Maximum bonding strength at two and one-half minutes). Surgical glue is resistant to water, but it will slough off faster if it is being held in the shower or washing dishes for at least 5 days (Equivalent in strength to healed tissue at seven days post repair). On the other hand, Group B (subcuticular group) was instructed for post-operative wound care e.g., to always keep wound dressing dry and clean and in case it got wet, it was to be dressed in an aseptic non-touch technique.

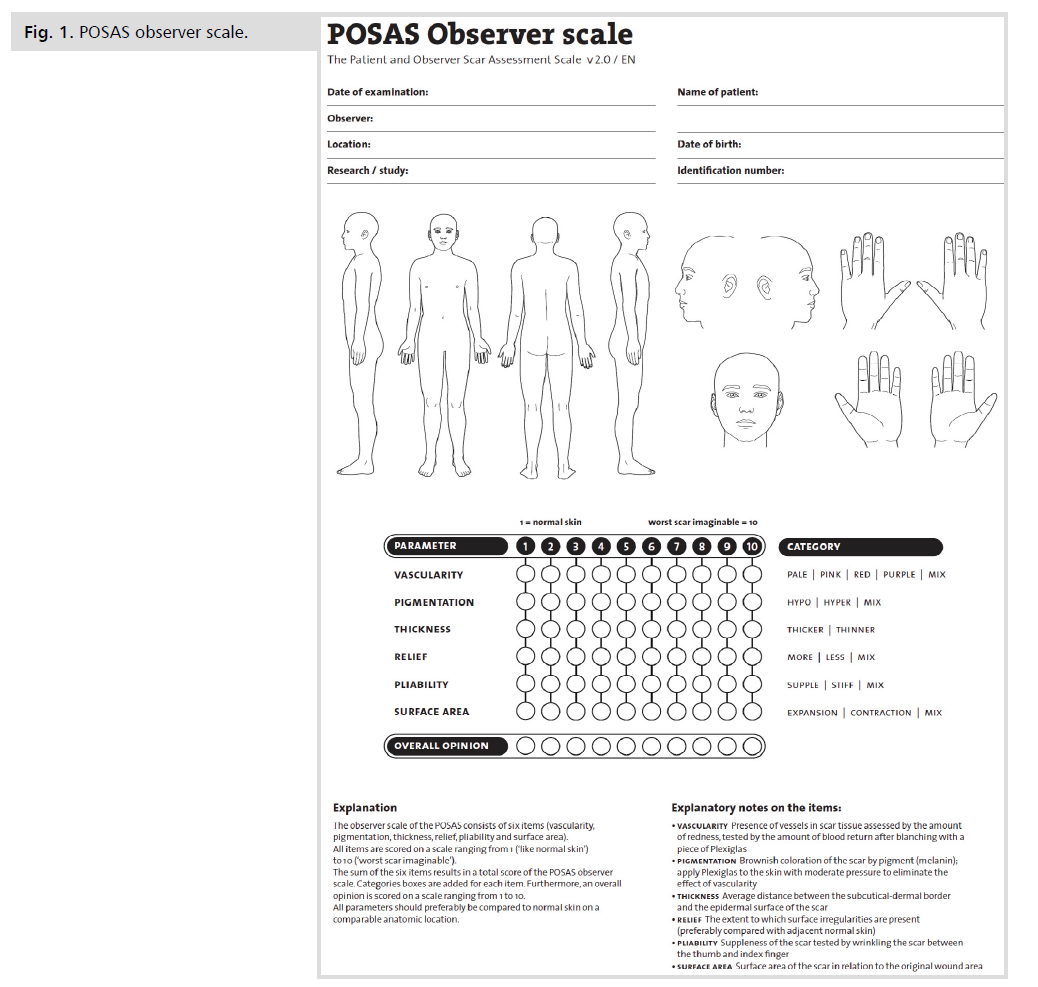

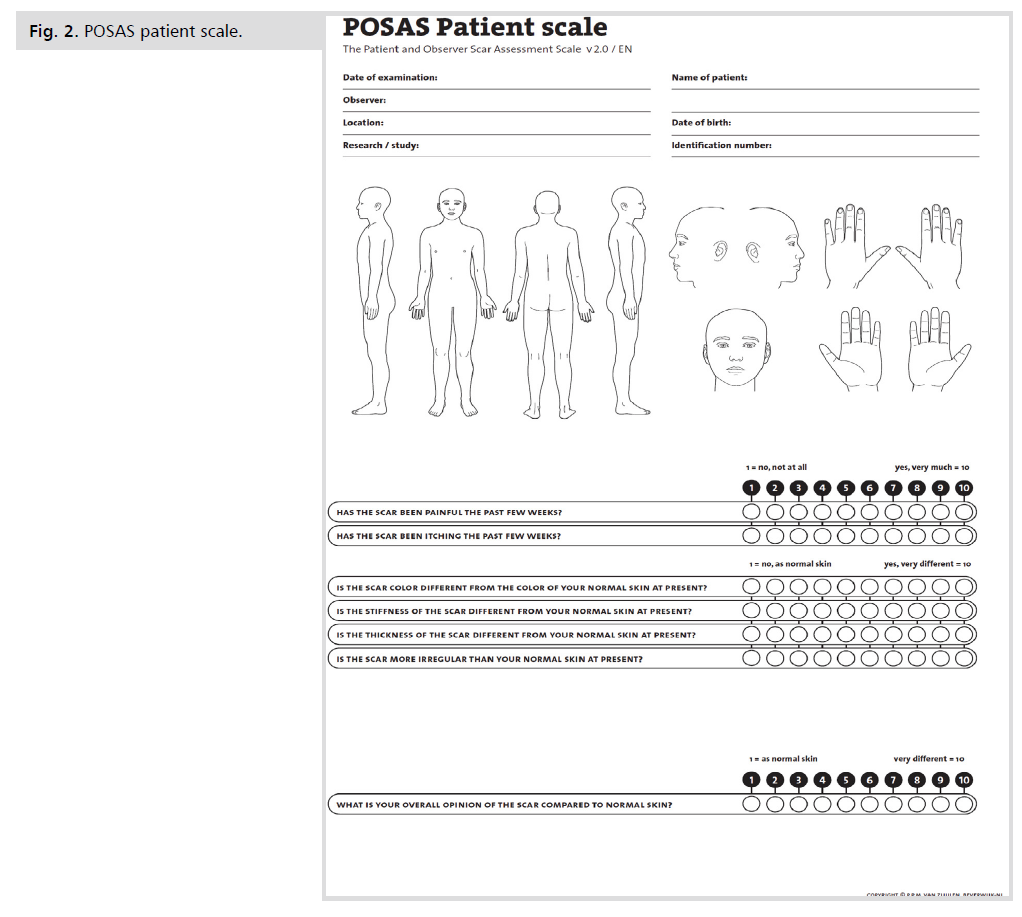

The appearance of the scars was evaluated one week, one month and 6-month later after the CD by both the patient and the physician. For scar evaluation, a validated scale; POSAS, the Patient and Observer Scar Assessment Scale (POSASv2.0) were used. Both scales consist of 6 items and every item is assessed by 10-point score with 10 indicating the worst imaginable scar or sensation. The lowest score is ‘1’ and corresponds to the situation of normal skin (normal pigmentation, no itching etc.), and goes up to the worst imaginable. Moreover, both the patient and the observer were asked to give their overall opinion on the appearance of the scar. The overall opinion is not a part of the total score of the observer and patient Scale of the POSAS [7].

In the POSAS observer scale v2.0, observers rated vascularity, pigmentation, pliability, thickness, relief, and surface area. The directions for use of the different parameters of the observer scale POSAS v2.0 are as follows (all parameters should be compared to normal skin at a comparable anatomical site whenever possible) [8] (Fig. 1.).

Figure 1: POSAS observer scale.

The POSAS v2.0 patient scale contains six questions applying to pain, itching, color, pliability, thickness, and relief. Because it is too difficult for patients to make the distinction between pigmentation and vascularity, both characteristics were captured in one item: color [9] (Fig. 2.).

Figure 2: POSAS patient scale.

The surgeon satisfaction with each closure method (glue vs. sutures) was assessed by the surgeons' satisfaction scale which is based on 3 questions asked immediately upon completion of surgery: (1) How comfortable were you with the technique? (Not at all [1] to totally comfortable [5]); (2) Was the estimated total operating time longer using glue compared to skin closure with sutures? (Not at all [1] to yes, a lot longer [5]); and (3) were you satisfied with the final closure appearance? (Not at all [1] to yes, very satisfied [5]) [6]. The surgeons did not participate in the recruitment process. They operated using glue or sutures according to the patient randomization schedule.

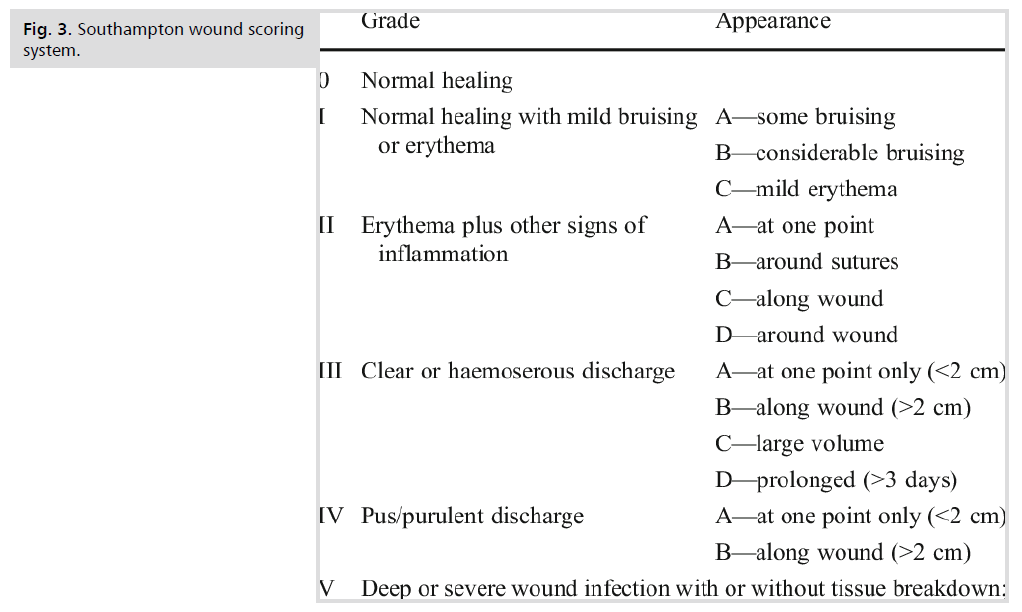

Surgical site infection (SSI) (manifested by e.g., serous discharge, pus and/or erythema) was assessed by Southampton wound scoring system (Fig. 3.).

Figure 3: Southampton wound scoring system.

Wound disruption and/or wound dehiscence (hematoma or seroma) were also assessed. The duration of skin closure was measured in minutes.

Using PASS program, setting alpha error at 5% and power at 80% result from previous study [6] showed that the mean Observer Scar Assessment Scale (OSAS) in glue group was 12.4 ± 5.6 compared to 11.7 ± 5.2 in suture group. Group sample sizes of 36 and 36 achieved 80% power to detect non-inferiority using a one-sided, two-sample t-test. The margin of non-inferiority was -2.500. The true difference between the means was assumed to be 0.700. The significance level (alpha) of the test was 0.05000. The data were drawn from populations with standard deviations of 5.200 and 5.600 (Fig. 4.).

Figure 4: Consort Flow Chart.

A total of 80 pregnant patients who underwent elective LSCS met the inclusion/exclusion criteria of the study. 40 participants were allocated to the glue group with one patient in group A (glue) did not receive the allocated intervention due to hardening of the glue becoming unusable. The other 40 participants were allocated to the suture group. Maternal demographic data were similar in both groups (p > 0.05) (Tab. 1 and Tab. 2.).

| Variables | Cases group | Control group | Test value | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. = 40 | No. = 39 | ||||

| Age (years) | Mean ± SD | 28.68 ± 4.41 | 30.00 ± 5.35 | -1.203• | 0.233 |

| Range | 21 – 40 | 21 – 40 | |||

| BMI | Mean ± SD | 26.50 ± 1.42 | 26.71 ± 1.43 | -0.640• | 0.524 |

| Range | 23.5 – 28.7 | 23.4 – 28.9 | |||

| Previous abdominal scar |

Median (IQR) | 1 (0.5 – 2.5) | 2 (1 – 3) | -1.574≠ | 0.115 |

| Range | 0 – 4 | 0 – 6 | |||

Tab. 1. The demographic data among the two groups of the study.

| POSAS Observer scale | Cases group | Control group | Test value | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. = 40 | No. = 39 | ||||

| Vascularity | Mean ± SD | 2.05 ± 0.32 | 2.79 ± 0.62 | -5.813≠ | 0.000 |

| Range | 1 – 3 | 2 – 5 | |||

| Pigmentation | Mean ± SD | 2.13 ± 0.40 | 2.21 ± 0.52 | -0.624≠ | 0.532 |

| Range | 1 – 3 | 1 – 4 | |||

| Thickness | Mean ± SD | 1.92 ± 0.57 | 2.33 ± 0.70 | -2.737≠ | 0.006 |

| Range | 1 – 3 | 1 – 4 | |||

| Relief | Mean ± SD | 1.63 ± 0.54 | 1.97 ± 0.74 | -2.139≠ | 0.032 |

| Range | 1 – 3 | 1 – 4 | |||

| Pliability | Mean ± SD | 1.78 ± 0.53 | 1.95 ± 0.76 | -0.935≠ | 0.350 |

| Range | 1 – 3 | 1 – 4 | |||

| Surface area | Mean ± SD | 2.28 ± 0.60 | 2.31 ± 0.47 | -0.087≠ | 0.930 |

| Range | 1 – 3 | 2 – 3 | |||

| Overall opinion | Mean ± SD | 2.20 ± 0.41 | 2.36 ± 0.58 | -1.193≠ | 0.233 |

| Range | 2 – 3 | 2 – 4 | |||

Tab. 2. The POSAS observer scale among the two groups of the study./p>

Regarding the primary outcome, there was highly significant statistical difference regarding vascularity and thickness between the two groups favoring the glue group with P-value 0.000 and 0.006, respectively. Besides, there was statistically significant difference regarding relief parameter with P-value 0.032. However, there was no statistically significant difference between the two groups regarding the overall opinion (Tab. 3.).

| POSAS Patient scale | Cases group | Control group | Test value | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. = 40 | No. = 39 | ||||

| Pain in the scar | Mean ± SD | 2.30 ± 0.46 | 3.51 ± 0.79 | -6.599≠ | 0.000 |

| Range | 2 – 3 | 2 – 6 | |||

| Itching of the scar | Mean ± SD | 1.43 ± 0.50 | 1.79 ± 0.62 | -2.687≠ | 0.007 |

| Range | 1 – 2 | 1 – 3 | |||

| Color difference at the scar | Mean ± SD | 2.47 ± 0.51 | 2.59 ± 0.55 | -0.889≠ | 0.374 |

| Range | 2 – 3 | 2 – 4 | |||

| Stiffness of the scar | Mean ± SD | 1.97 ± 0.48 | 2.23 ± 0.63 | -2.071≠ | 0.038 |

| Range | 1 – 3 | 1 – 3 | |||

| Thickness of the scar | Mean ± SD | 2.10 ± 0.59 | 2.26 ± 0.60 | -1.031≠ | 0.302 |

| Range | 1 – 3 | 1 – 4 | |||

| Irregularity of the scar | Mean ± SD | 2.25 ± 0.54 | 2.44 ± 0.64 | -1.220≠ | 0.223 |

| Range | 1 – 3 | 1 – 4 | |||

| Overall opinion | Mean ± SD | 2.35 ± 0.48 | 2.62 ± 0.75 | -1.598≠ | 0.110 |

| Range | 2 – 3 | 2 – 5 | |||

Tab. 3. The POSAS patient scale among the two groups of the study.

There was highly statistically significant difference in case group than control group regarding whether the scar has been painful and itching or not. Besides, there was statistically significant difference in case group than control group regarding stiffness of the scar compared to normal skin at present. However, there was no statistically significant difference regarding the overall opinion in both case and control groups (Tab. 4.).

| Variables | Cases group | Control group | Test value | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. = 40 | No. = 39 | ||||

| Pre-operative Hemoglobin |

Mean ± SD | 11.24 ± 0.62 | 11.12 ± 0.60 | 0.816• | 0.417 |

| Range | 10.1 – 12.3 | 10.1 – 12.3 | |||

| Post-operative Hemoglobin |

Mean ± SD | 10.49 ± 0.66 | 10.43 ± 0.66 | 0.402• | 0.689 |

| Range | 9.5 – 11.8 | 9.5 – 11.8 | |||

| Wound disruption | No | 40 (100.0%) | 39 (100.0%) | – | – |

| Yes | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | |||

| Wound dehiscence | No | 38 (95.0%) | 37 (94.9%) | 0.001* | 0.979 |

Tab. 4. Pre-operative hemoglobin, post-operative hemoglobin, and wound complications.

There was no statistically significant difference between two groups regarding pre-operative and post-operative hemoglobin. Also, there was no statistically significant difference between case and control groups regarding wound dehiscence and disruption (Tab. 5.).

| Surgeon satisfaction scale | Cases group | Control group | Test value | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. = 40 | No. = 39 | ||||

| Comfortability with the technique |

Not at all | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 56.977* | 0.000 |

| Slightly comfortable | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | |||

| Moderately comfortable | 0 (0.0%) | 2 (5.1%) | |||

| Comfortable | 2 (5.0%) | 33 (84.6%) | |||

| Totally comfortable | 38 (95.0%) | 4 (10.3%) | |||

| Estimated total operating time with the material used |

Not at all | 40 (100.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 79.000* | 0.000 |

| Slightly longer | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | |||

| Moderately longer | 0 (0.0%) | 11 (28.2%) | |||

| Longer | 0 (0.0%) | 28 (71.8%) | |||

| A lot longer | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | |||

| Satisfaction with the final closure appearance |

Not at all | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 35.665* | 0.000 |

| Not satisfied | 0 (0.0%) | 1 (2.6%) | |||

| Neither | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | |||

| Satisfied | 6 (15.0%) | 31 (79.5%) | |||

| Very satisfied | 34 (85.0%) | 7 (17.9%) | |||

| Surgical Site infection | Normal healing | 38 (95.0%) | 34 (87.2%) | 4.210* | 0.378 |

| Some bruising | 1 (2.5%) | 3 (7.7%) | |||

| Considerable bruising | 1 (2.5%) | 0 (0.0%) | |||

| At one point only (<2 cm) | 0 (0.0%) | 1 (2.6%) | |||

| Along wound (>2 cm) | 0 (0.0%) | 1 (2.6%) | |||

Tab. 5. The surgeons’ satisfaction scale.

There was highly statistically significant difference in case group than control group regarding the comfortability with the technique used, the operating time with the material used and the satisfaction with the final closure appearance (Tab. 6.).

| Surgical Site infection | Normal healing | 38 (95.0%) | 34 (87.2%) | 4.210* | 0.378 |

| Some bruising | 1 (2.5%) | 3 (7.7%) | |||

| Considerable bruising | 1 (2.5%) | 0 (0.0%) | |||

| At one point only (<2 cm) | 0 (0.0%) | 1 (2.6%) | |||

| Along wound (>2 cm) | 0 (0.0%) | 1 (2.6%) |

Tab. 6. The Surgical Site infection(s).

There was no statistically significant difference in the surgical site infection with P-value=0.378 (Tab. 7.).

| Variables | Cases group | Control group | Test value | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. = 40 | No. = 39 | ||||

| Duration of closure in minutes |

Mean ± SD | 2.93 ± 0.47 | 10.68 ± 1.19 | -38.323• | 0.000 |

| Range | 1.83 – 4.03 | 8.33 – 13.08 | |||

| Cost (Egyptian pound) | 50 | 0 (0.0%) | 39 (100.0%) | 79.000 | 0.000 |

| 485 | 40 (100.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | |||

Tab. 7. The duration of closure of the skin at CD and the cost of the material used in each group.

Regarding the time needed in minutes for closure of the skin, there was highly significant difference in the duration of closure of the skin in case group than in control group. However, there was highly statistically significant difference regarding the cost favoring control group (Tab. 8.).

| Follow up | Cases group | Control group | Test value | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| After 1 month | No. = 39 | No. = 38 | |||

| Observer | Mean ± SD | 1.51 ± 0.56 | 1.68 ± 0.53 | -1.444≠ | 0.149 |

| Range | 1 – 3 | 1 – 3 | |||

| Patient | Mean ± SD | 1.69 ± 0.57 | 1.74 ± 0.50 | -0.448≠ | 0.654 |

| Range | 1 – 3 | 1 – 3 | |||

| After 6 months | No. = 37 | No. = 36 | |||

| Observer | Mean ± SD | 1.00 ± 0.00 | 1.03 ± 0.17 | -1.014≠ | 0.311 |

| Range | 1 – 1 | 1 – 2 | |||

| Patient | Mean ± SD | 1.05 ± 0.23 | 1.14 ± 0.35 | -1.222≠ | 0.222 |

| Range | 1 – 2 | 1 – 2 | |||

Tab. 8. Follow up study participants after 1 month and 6 months.

Follow up of study participants 1 month and 6 months after the procedure showed that there was no statistically significant difference in the overall opinion of the scar appearance.

Cesarean Delivery is the most common major surgery in women worldwide [1]. However, despite its prevalence, data regarding many aspects of the preferred surgical technique at skin closure are sparse. It influences postoperative pain, wound healing, cosmetic outcome, and surgeon and patient satisfaction [10].

Currently, there is no evidence on the best method for skin closure in cesarean sections, so the selection is based on the preference of the surgeon [11,12].

The aim of the study was to compare between using of glue and running monofilament subcuticular suture technique in skin closure at cesarean delivery regarding cosmetic appearance.

Regarding the demographic data, there was no statistically significant difference between the two groups regarding age and BMI with P-value 0.233 and 0.524, respectively.

The primary outcome of the study was evaluation of the scar made by the skin incision and for objective assessment, the evaluation was made by the patient and observer scar assessment scale POSAS. The POSAS observer scale was assessed one week after the procedure and despite that there was significant difference between the two groups favoring the glue group at two items of assessment which are the vascularity and thickness with P-value of 0.000 and 0.006 respectively, there was no significant difference between the two groups regarding the overall opinion with P-value of 0.233. Regarding the POSAS patient scale, there was significant difference between the two groups favoring the glue group regarding two items of the assessment scale which are the pain and itching with P-value of 0.000 and 0.007 respectively; however, there was no significant difference between the two groups regarding the overall opinion with P-value of 0.110. Kwon et al., obtained similar results in their retrospective study using a different scale which is the Vancouver scar scale (VSS) which has similar parameters to the POSAS scale. There was no significant difference between the two groups with P-value 0.858 [13]. Daykan et al., obtained similar results as well in their study; the authors used the POSAS to evaluate the scar eight weeks after the cesarean section and there was no significant difference between the glue group and the suture group regarding both the patient scar assessment scale (P-value: 0.710) and the observer scar assessment scale (P-value: 0.568) [6].

As for previous abdominal scars, there was no significant difference between the two groups regarding the number of previous abdominal scars with P-value of 0.115. Such results were similar to that obtained by Kwon et el., as there was no significant difference between the study groups of their retrospective study; 209 patients had their skin closed via tissue adhesive n-butyl-2-cyanoacrylate (NBCA) while 208 patients had their skin closed by suture and there was no significant difference between the two groups regarding the number of previous cesarean deliveries with P-value of 0.562 [13].

The pre-operative hemoglobin (gm/dl) was evaluated in our study and there was no significant difference between the Dermabond group and the Monocryl group (11.24 ± 0.62 Vs 11.12±0.60 with P-value 0.417). The same was observed with post-operative hemoglobin as there was no significant difference between the two groups (10.49±0.66 Vs 10.43±0.66 with P-value 0.689). Such results were similar to that obtained by Daykan et al., who evaluated 104 patients scheduled for cesarean delivery in their study [6].

Regarding the complications, the surgical site infection was assessed using the Southampton wound scoring system. Among the glue group, there were 2 cases which were detected at the one-week postpartum visit with one being graded as 1A i.e., mild bruising while the other was graded as 1B i.e., considerable bruising; both were managed conservatively with topical anti-inflammatory agents and topical antibiotics for one week with no further sequelae. As for the suture group, 3 cases were graded as 1B detected at the one week postpartum visit with the same management as glue group while 1 case was graded as 3A i.e., clear discharge at one point only (<2 cm) which was detected 5 days post-operatively and it was managed conservatively with frequent dressing, culture and sensitivity from the discharge and topical antibiotics for 2 weeks; the last case was graded as 3B i.e., clear discharge along the wound and the same management as 3A was applied. Our results showed that there was no significant difference between the two groups regarding surgical site infection with P-value of 0.378. Siddiqui et al. showed similar results in their retrospective study; the authors used the center for disease control (CDC) criteria in characterizing surgical site infection and among the Dermabond group (n=100), there were 2 cases of superficial site infection and among the suture group (n=56), there was one case of SSI with no cases of deep or organ space infection recorded [4]. Kwon et al., obtained similar results as well as there was no statistically significant difference between the two groups regarding wound infection which was defined as purulent drainage, cellulitis, and abscess requiring antibiotics [13].

As for other complications which are associated with the procedure, there were no reported cases of allergy to the material used in skin closure in either group. As for wound dehiscence, there was no significant difference between the two groups with P-value of 0.979. Regarding the analysis of the cases complicated by wound dehiscence, there were 2 cases of wound dehiscence in the glue group and in both cases the dehiscence was limited to the skin and subcutaneous tissue with no fascial dehiscence; the first case was detected just 2 hours after the procedure, and it was probably due to faulty technique. The dehiscence was about 2 cm long and it was reapproximated with 2 simple stitches of polyprolene suture. The second one was detected at the 1 week follow up visit and it was about 3 cm in length; it was managed by saline irrigation thrice daily and it was left to heal by secondary intention, and it healed completely after 3 weeks. Regarding the suture group, 2 cases of wound dehiscence were recorded and both were detected at the 1 week follow up visit; the first one measured about 4 cm and it was managed by removal of the subcutaneous stitches, saline irrigation of the wound thrice daily with application of Iruxol ointment afterwards and then the skin edges were reapproximated by 3 simple stitches of polyprolene suture under local anesthesia while the second one was 2 cm in length and managed by saline irrigation thrice daily and left to heal by secondary intention. Our results regarding wound disruption were similar to that obtained by Daykan et al., who reported that there was no statistically significant difference between the glue group and the suture group regarding wound disruption with P-value of 0.153 (6). Tan et al., also obtained similar results in their pilot study; the study included 50 cases in the Dermabond group and 47 cases in the suture group and there were no cases of wound dehiscence in either group [14].

The duration of skin closure was measured in minutes and there was significant difference between the two groups regarding the duration (glue group: 2.93 ± 0.47 Vs suture group: 10.68 ± 1.19 with P-value 0.000 which represents highly significant difference). Such difference explains the surgeon answer to the second question of the surgeon satisfaction scale which showed highly significant difference between the two groups favoring the glue group.

The cost of the material used in skin closure was also measured in Egyptian pound and there was highly significant difference between the two groups favoring the suture group.

Cases who participated in the study were followed up at 1 month and 6 months post-operatively to monitor the condition of the scar. Assessment of the scar was made by the POSAS observer and patient scale. Among the glue group, 38 cases attended the follow up at 1 month and 36 cases attended the follow up after 6 months while 39 cases of the suture group attend the 1 month follow up and 37 cases attend the 6 months follow up. After 1 month, there was no statistically significant difference between the two groups regarding the POSAS observer scale or POSAS patient scale with P-value of 0.149 and 0.654, respectively. The same was observed after 6 months as there was no significant difference between the two groups regarding either POSAS observer scale or POSAS patient scale with P-value of 0.311 and 0.222, respectively.

The surgeon satisfaction with the glue was assessed by using the surgeon satisfaction scale and compared with the subcuticular closure, there was significant difference between the two groups in all items of assessment which are the comfortability with the technique, estimated total operative time with the material used and satisfaction with the final closure appearance. Our results were similar to Daykan et al. [6], regarding the first arm of the scale which is the comfortability with the technique; however, there was no significant difference between the two groups regarding the other 2 arms which are the total operative time with the material used and the final closure appearance. Such discrepancy can be attributed to, in our study, there was only one surgeon who was responsible for skin closure either by Dermabond® or Monocryl® suture while there were 5 surgeons who participated in the study by Daykan et al. [6], which means that five surgeons with different opinions were subjected to the surgeon satisfaction scale. Also, in our study, obese patients i.e., patients with BMI ≥ 30 kg/m2 were excluded. However, Daykan et al. [6] did not put BMI as a parameter in their inclusion/ exclusion criteria, So, with obese and morbidly obese cases being among their analyzed patients, that could affect the duration of closure and the final appearance especially with the presence of abdominal pannus.

Our data suggests that Dermabond® glue is an effective method of skin closure after cesarean delivery via Pfannenstiel incision in patients with low risk for surgical site infection. It is associated with excellent cosmetic profile with No higher risk of surgical site infection, wound dehiscence or disruption compared with suture closure. However, it is not cost effective and so it is not suitable for hospitals with limited resources as long as the cost remains so high compared with the conventional suture.

Dermabond® glue is an effective method of skin closure after cesarean delivery via Pfannenstiel incision in patients with low risk for surgical site infection. It is associated with excellent cosmetic profile with No higher risk of surgical site infection, wound dehiscence or disruption compared with suture closure. In addition to that, the comfortability of surgeon with technique, estimated total operating time, duration of closure in minutes and satisfaction with the final closure appearance were also better. However, it is not cost effective and so it is not suitable for hospitals with limited resources if the cost remains so high compared with the conventional suture.

Copyright:This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.