Research Article - (2023) Volume 0, Issue 0

Mechanical dilatation of the cervix transabdominally in elective cesarean section for reducing postpartum endometritis

Nadim A, Eissa Y*, El Sayed M and Maaty AReceived: 02-May-2023, Manuscript No. gpmp-24-126589; Editor assigned: 04-May-2023, Pre QC No. P-126589; Reviewed: 15-May-2023, QC No. Q-126589; Revised: 22-May-2023, Manuscript No. R-126589; Published: 01-Jun-2023

Abstract

Aim: This study aims to assess the effect of transabdominal cervical dilatation during elective CS in decreasing the incidence of postpartum endometritis.

Patients and methods: It was a randomized controlled clinical trial conducted at the labor ward of the Ain-Shams University Maternity Hospital, in the period from August 2020 to February 2021. The study was include 220 patients who are consenting to be recruited in the study and fulfilling the inclusion criteria. If any of the patients refused to continue in the study or any major complication occur which makes the patient not fit in this study as she didn’t meet the inclusion criteria, this patient was considered as a drop out which is included in sample size calculation. The patients will be divided into 2 groups, Group (A) (N=110): CS with mechanical cervical dilatation and Group (B) (N=110): CS without cervical dilatation.

Results: There was no statistically significant between both groups regarding postpartum endometritis or wound sepsis. There was no statistically significant difference between both groups regarding hemoglobin drop or postoperative hospital stay. None of patients in both groups developed cervical injury during transabdominal cervical dilatation during elective CS. There was no statistically significance difference between both groups regarding transabdominal mechanical dilatation of cervix during elective CS and cervical injury during dilatation.

Conclusion: Dilatation of the cervix during cesarean section compared with no dilatation of the cervix did not influence the risk of postpartum endometritis, wound infection, drop between preoperative and postoperative hemoglobin and postoperative hospital stay.

Keywords

Mechanical dilatation of the cervix; Elective cesarean section; Postpartum endometritis

Introduction

Cesarean delivery is among the most frequently performed surgical procedures by obstetricians. Postoperative infectious complications following cesarean deliveries can significantly affect a woman's recovery to her usual activities. Even with the common practice of administering prophylactic antibiotics, infections after surgery continue to be an issue in cesarean deliveries[1].

Inflammation of the uterine lining, known as endometritis, may occur when vaginal bacteria enter the uterus during childbirth, leading to an infection within six weeks after delivery (postpartum endometritis). Symptoms of endometritis include fever, tenderness in the pelvic area, and foul-smelling vaginal discharge following childbirth. It can result in serious complications such as the development of pelvic abscesses, the formation of blood clots, infection of the peritoneum, which is the delicate tissue that lines the abdomen and covers abdominal organs, and a systemic inflammatory response known as sepsis[2].

Infectious morbidity is the most common complication associated with cesarean deliveries. Among women who undergo cesarean sections, 5â??24% experience clinically significant fevers, while 6â??21% are diagnosed with uterine infections, such as endomyometritis or endometritis. Additionally, between 1â??5% of cases involve more severe pelvic infections, including abscesses, and 2â??9% may experience issues related to the surgical incision [3].

Post-cesarean endometritis and infectious morbidity occur when bacteria from the vagina and cervix ascend to infect the uterus, contributing to antibiotic prophylaxis failure during cesarean deliveries [4].

Approaches to reduce the risk of postoperative infections and other complications have included adjustments to surgical methods, the practice of changing gloves during the procedure, different techniques for placental delivery, and modifying the position of the uterus while repairing the uterine incision. Nonetheless, none of these investigations have assessed the dilation of the cervix during elective Cesarean sections (C.S.) [5].

Some surgeons perform routine cervical dilatation during elective cesarean sections to help the lochia exit from a uterus that has not undergone labor in the immediate postoperative phase [6].

A mechanical dilatation of the cervix at CS is deï¬ned as an artificially dilated using fingers, sponge forceps, or other instruments during an elective cesarean section. A significant concern related to cervical dilation in a non-labor uterus is the potential risk of infection ascending from the vagina to the uterus[7].

Furthermore, cervical dilation might lead to the formation of a false passage or bleeding resulting from cervical damage. Nevertheless, an undilated cervix could hinder the expulsion of lochia after an elective cesarean section, resulting in the retention of lochia, which could serve as a potential breeding ground for bacteria and may result in puerperal infections of the genital tract[8].

This study aims to assess the effect of transabdominal cervical dilatation during elective CS in decreasing the incidence of postpartum endometritis.

Patients and Methods

A randomized controlled clinical trial was conducted at the labor ward of the Ain-Shams University Maternity Hospital from August 2020 to February 2021. 220 patients met all inclusion and exclusion criteria and were included in the study.

The patients were divided into 2 groups:

• Group (A) (N=110): CS with mechanical cervical dilatation.

• Group (B) (N=110): CS without cervical dilatation.

• Study Population: (N=220)

Inclusion criteria:

• Age group (20–35 years old).

• BMI between (20–30 kg/m2).

• Elective Cs (primary or repeated CS).

• Single, viable, term pregnancy, expected fetal weight (2.5 –3.5kg).

Exclusion criteria:

Medical or obstetric conditions that could put the patient at risk for uterine atony, postpartum hemorrhage or infection, such as:

• Anemia (Hb level ≤ 10 gm %) [9].

• Abruptio placenta and Placental site abnormalities eg: Placenta Previa (Placenta accreta, Placenta Increta, Placenta Percreta) [9].

• Emergency Cesarean section.

• Over distended uterus eg: multiple gestation, polyhydramnios, fetal macrosomia (ÃÂ??4.5kg) [10].

• Intra Uterine Fetal Death [11].

• History of Pelvic Inflammatory Disease [12].

• Immune suppressive drugs eg: Corticosteroids [13].

• Autoimmune diseases or immunocompromised disease eg: DM [12].

• Peri-operative blood transfusion or massive blood loss (ÃÂ??3 Liters) [11].

• Rupture of membranes, intra-ammonitic infection and fever during admission (ÃÂ??38ºc) [12].

• Previous cervical surgeries eg: Loop electrical excision procedure.

Ethical considerations:

• â?¢ Informed verbal consent outlining the details of the procedure was secured from patients before they were included in the study.

• The research was carried out in accordance with the regulations set forth by the Department of Obstetrics & Gynecology at the Faculty of Medicine's ethical and scientific committee.

• The research adhered to the guidelines established by the Ain Shams University ethical and scientific committee.

Study Tools and Procedures

History taking:

• All historical information was collected, such as age, duration of the marriage, Current status (any existing medical or surgical illnesses), Medical history (including previous health issues), Obstetric history (covering Parity, Gestational age, and any complications during pregnancy), Contraceptive history, and Menstrual history.

Clinical examination:

General examination:

1) Evaluation of the patient's overall health status (chronic fatigue, such as in individuals with anemia).

2) Calculation of Body Mass Index (BMI) recorded in kg/m2.

3) Observation of skin tone, for instance, pallor in individuals with anemia.

4) Collection of vital signs (pulse, blood pressure, temperature).

5) Cardiac and pulmonary auscultation to rule out any contraindications for anesthesia.

Abdominal examination: Evaluation of the fundal height, fetal position, presentation, amniotic fluid volume, fetal heart sound detection, and any previous surgical scars, if they exist.

Vaginal examination: To rule out changes in the cervix, rupture of membranes, and the presence of cervical polyps or fibroids.

Investigations

Ultrasound examination: A 2D ultrasound was performed transabdominally to evaluate fetal viability, the number of fetuses, and gestational age, exclude any uterine or fetal abnormalities, assess fetal weight, and determine the precise location of the placenta.

Baseline laboratory investigations: A venous blood sample was collected from all participants to evaluate:

• Hemoglobin and hematocrit levels.

• Total white blood cell count.

• Platelet counts.

• Rh factor and blood type.

• Viral markers (HBs Ag, HCV Ab).

• Coagulation profile (PT, PTT, and INR).

All cesarean sections were conducted by a senior registrar qualified to perform elective cesarean deliveries.

Operative steps:

1) All operations were performed under regional spinal anesthesia.

2) Sterilization of urethral meatus and catheterization under aseptic conditions.

3) Vaginal toilet was done for all patients with the povidone-iodine solution before the operation.

4) Scrubbing the abdomen was done by using a povidone-iodine solution of 10%.

5) Pfannenstiel incision of the skin was done(Any scar of the previous section was removed in both groups) followed by the opening of the abdominal wall in layers, then lower transverse uterine incision and delivery of the baby (without assistance by using forceps) followed by complete delivery of the placenta by controlled cord traction.

6) Oxytocin (5 IU by slow intravenous injection) was used to encourage uterus contraction and decrease blood loss[13].

7) In the cervical dilatation group, the surgeon performed the cervical dilatation (by gently inserting the double-gloved index ï¬ÂÂnger or a straight artery) into the cervical canal of the patients after the extraction of placenta and membranes. The outer glove was removed after this procedure.

8) The uterus was sutured in two layers using vicrylÃÂ?® 1/0 sutures, followed by closure of the rectus sheath and closure of the subcutaneous layer (in case its thickness is ÃÂ??2cm) with interrupted absorbable sutures [14].

9) The skin was sutured by a non-absorbable polypropylene suture 0/2 (subcuticular).

10) Vaginal toilet and Speculum examination was done to exclude any cervical tear.

11) The wound was dressed postoperatively and was changed after 48 hours.

Post-operative care:

1) The postoperative care provided to both groups was identical.

2) All patients were administered Non-Steroidal Anti-Inflammatory drugs, specifically Diclofenac SodiumÃÂ?® at a dosage of 75mg IM (one ampule) immediately after surgery, followed by another ampule 12 hours later.[15].

3) The patients' vital signs (pulse, blood pressure, temperature) were recorded four times daily throughout their hospital stay.

4) Urine Foley catheters were removed six hours after surgery, and patients began consuming clear fluids[16].

5) A venous blood sample for a complete blood count was taken 24 hours following the operation.

6) Regular antipyretics were not administered to avoid masking any potential postoperative fever.

7) Before discharge:

• The patients were informed about warning signs that could indicate endometritis and were provided with a contact number to call if they noticed any of these symptoms.

• Patients received instructions on how to care for their postoperative wounds, emphasizing the importance of keeping the dressing dry and clean; if it became wet, it should be redressed using aseptic non-touch techniques.

Sample size justification:

According to data derived from earlier research, the likelihood of postpartum endometritis occurs in 9% of cases without cervical dilation, whereas it is 0% in cases with cervical dilation, with an alpha error of 5% and a study power of 80%. A total of 220 patients will be required for the study, split evenly into 110 patients for each group. The software used for calculating the sample size is Stata 15.

Statistical methods:

The chi-square test or Fisher Exact test was utilized to compare categorical data, while continuous data were analyzed using the Student t-test or Mannâ??Whitney U test. Statistical analyses were conducted using SPSS version 20.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY) and SAS version 9.3 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC), with a p-value of less than 0.05 regarded as statistically significant.

Randomization:

The patients who were included in the study were assigned randomly into two groups, each consisting of 110 patients, using a sealed opaque envelope method. To guarantee that every patient meeting the inclusion criteria had an equal opportunity to participate, randomization in this study was facilitated by a table of random numbers generated by a computer program(using www.randomization.com).

Allocation and concealment:

Participants in the study were assigned to groups through a computer-generated randomization process using MedCalc version 13. Two hundred and twenty opaque envelopes were sequentially numbered, and each envelope contained the corresponding letter indicating the assigned group based on the randomization table. All envelopes were then sealed and placed in a single box. When the initial patient arrived, the first envelope was opened, and the patient was assigned according to the letter found inside, continuing in this manner for subsequent patients.

Elimination of bias:

• Laboratory samples were done in the same laboratory preoperative and postoperative.

• Same type of surgical sutures were used to all patients.

• All C.S were performed by a senior registrar.

• All patients received the same kind of antibiotics.

• Urinary catheter was removed after 6 hours postoperative to decrease risk of UTI.

• Speculum examination of cervix after vaginal toilet to exclude any tear.

Data management and analysis:

The gathered data was reviewed, classified, organized, and entered into a computer using the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS 20). The data was displayed and appropriate analyses were conducted based on the nature of the data collected for each parameter.

• Descriptive statistics:

• Mean Standard deviation (± SD) and range for numerical data.

• Frequency and percentage of non-numerical data.

• Analytical statistics:

• Student T Test was used to assess the statistical significance of the difference between two study group means.

• Chi-Square test was used to examine the relationship between two qualitative variables.

Fisher’s exact test: was used to examine the relationship between two qualitative variables when the expected count is less than 5 in more than 20% of cells.

Results

This study was conducted at Ain Shams University Maternity Hospital during the period between August 2020 and March 2021. 220 pregnant women having elective CS were enrolled in this study randomly allocated in two groups:

Group A (N=110 patient) CS with mechanical cervical dilatation

Group B (N=110 patient) CS without mechanical cervical dilatation

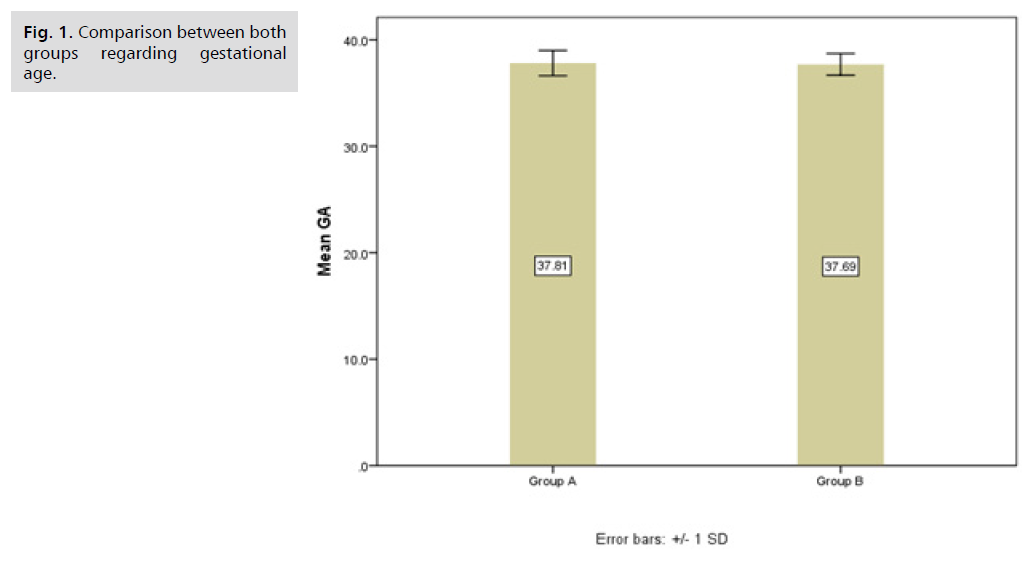

The results were as Tab. 1. shows parity and previous history of CS among group A and group B. There was no statistically significant difference between the two groups regarding parity and previous history of CS. Tab. 2. and Fig. 1. show a comparison between both groups regarding gestational age. There was no statistically significant difference between both groups regarding gestational age. Tab. 3. shows the comparison between both groups regarding fever, abdominal pain, and offensive vaginal discharge, which indicate postpartum endometritis diagnosis. There was no statistical significance between either group regarding the development of postpartum endometritis.

Fig 1. Comparison between both groups regarding gestational age.

| Group A With cervical dilatation |

Group B Without cervical dilatation |

Chi square test | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | % | N | % | X2 | p value | sig. | ||

| Parity | PG | 20 | 18.2% | 12 | 11.0% | 0.5 | 0.472 | NS |

| 1 | 18 | 16.4% | 30 | 27.5% | ||||

| 2 | 35 | 31.8% | 26 | 23.9% | ||||

| 3 | 20 | 18.2% | 23 | 21.1% | ||||

| 4 | 13 | 11.8% | 9 | 8.3% | ||||

| 5 | 4 | 3.6% | 8 | 7.3% | ||||

| 6 | 0 | 0.0% | 1 | 0.9% | ||||

| CS History | No | 16 | 14.55% | 19 | 17.3% | 0.57 | 0.455 | NS |

| Yes | 94 | 85.45% | 91 | 82.7% | ||||

Tab. 1. Parity and previous history of CS among group A and group B.

| Group A With cervical dilatation |

Group B Without cervical dilatation |

t test | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | SD | Mean | SD | t | p value | sig. | |

| GA | 37.81 | 1.19 | 37.69 | 1.02 | 0.810 | 0.419 | NS |

Tab. 2. Comparison between both groups regarding gestational age.

| Group A With cervical dilatation |

Group B Without cervical dilatation |

Fisher exact |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | % | N | % | p value | sig. | ||

| Fever | No | 109 | 99.1% | 109 | 99.1% | 1 | NS |

| Yes | 1 | 0.9% | 1 | 0.9% | |||

| Abdominal pain | No | 109 | 99.1% | 109 | 99.1% | 1 | NS |

| Yes | 1 | 0.9% | 1 | 0.9% | |||

| Offensive vaginal discharge | No | 109 | 99.1% | 109 | 99.1% | 1 | NS |

| Yes | 1 | 0.9% | 1 | 0.9% | |||

| Endometritis | No | 109 | 99.1% | 109 | 99.1% | 1 | NS |

| Yes | 1 | 0.9% | 1 | 0.9% | |||

Tab. 3. Comparison between both groups regarding fever, abdominal pain and offensive vaginal discharge which indicates postpartum endometritis diagnosis.

Tab. 4. shows the comparison between both groups regarding wound sepsis. There was no statistically significant between both groups regarding wound sepsis. Six patients in group A (with cervical dilatation) developed wound sepsis. Four patients in the form of seroma, three of them were small and eventually resolved spontaneous with no need for further intervention and one large seroma that required external drainage using syringe needle. One patients developed wound cellulitis that resolved with repeated dressing using topical antibiotic (bivatracin). One patient suffered from wound dehiscence that was treated by repeated dressing followed by secondary sutures.

| Cesarean wound infection | Group A | Group B | Chi square test. | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | % | N | % | P-value | sig. | |

| Present | 6 | 5.5 | 4 | 3.6 | 0.785 | NS |

| Absent | 104 | 94.5 | 106 | 96.4 | ||

Tab. 4. presents a comparison of wound sepsis between the two groups. There was no significant statistical difference observed between the groups concerning wound sepsis. Six patients in group A (with cervical dilatation) developed wound sepsis. Four patients in the form of seroma, three of them were small and eventually resolved spontaneous with no need for further intervention and one large seroma that required external drainage using syringe needle. One patients developed wound cellulitis that resolved with repeated dressing using topical antibiotic (bivatracin). One patient suffered from wound dehiscence that was treated by repeated dressing followed by secondary sutures.

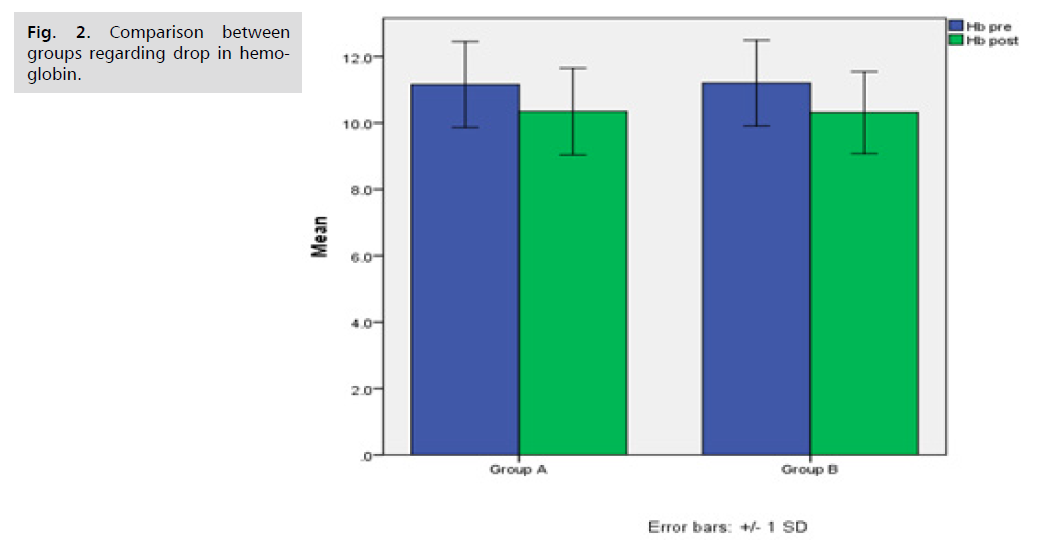

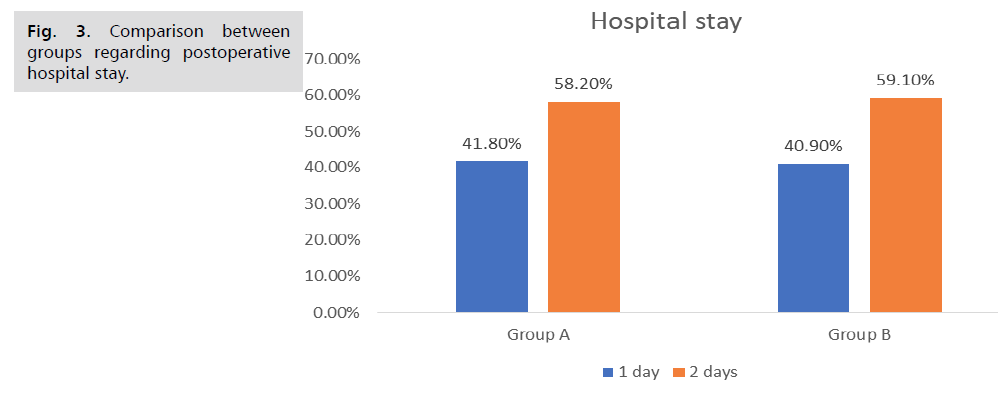

Tab. 5. and Fig. 2. shows the comparison between both groups regarding drop in haemoglobin. There was no statistically significant difference between both groups regarding drop in hemoglobin. Tab. 6. and Fig. 3. 1. shows the comparison between both groups regarding postoperative hospital stay. There was no statistically significance difference between both groups regarding postoperative hospital stay. Tab. 7. . shows the comparison between groups regarding cervical injury during dilatation. There was no statistically significance difference between both groups regarding cervical injury during dilatation. None of patients in both groups developed cervical injury during transabdominal cervical dilatation during elective cs.

Fig 2. Comparison between groups regarding drop in hemoglobin.

Fig 3. Comparison between groups regarding postoperative hospital stay.

| Group A With cervical dilatation |

Group B Without cervical dilatation |

t test | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | SD | Mean | SD | t | p value | sig. | |

| Hb pre | 11.2 | 1.3 | 11.2 | 1.3 | -0.247 | 0.805 | NS |

| Hb post | 10.3 | 1.3 | 10.3 | 1.2 | 0.149 | 0.882 | NS |

Tab. 5. Comparison between both groups regarding drop in hemoglobin.

| Group A With cervical dilatation |

Group B Without cervical dilatation |

Fisher exact | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | % | N | % | p value | sig. | ||

| Postoperative hos stay | 1 day | 46 | 41.8% | 45 | 40.9% | 1 | NS |

| 2 days | 64 | 58.2% | 65 | 59.1% | |||

Tab. 6. Comparison between both groups regarding postoperative hospital stay.

| Group A With cervical dilatation |

Group B Without cervical dilatation |

Fisher exact | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | % | N | % | p value | sig. | ||

| Cervical injury | No | 110 | 100.0% | 110 | 100.0% | - | |

Tab. 7. Comparison between groups regarding cervical injury during dilatation.

Discussion

This study is a Randomized controlled clinical trial which was carried at the labor ward of the Ain-Shams University Maternity Hospital, in the period from August 2020 to February 2021. 220 patients met all inclusion and exclusion criteria and were included in the study.

The patients were divided into 2 groups:

• Group (A) (N=110): CS with mechanical cervical dilatation.

• Group (B) (N=110): CS without cervical dilatation.

In this study one patient in group A (with cervical dilatation group) developed postpartum endometritis that was manifested by fever, abdominal pain and offensive vaginal discharge. The diagnosis was confirmed by complete blood picture showing leukocytosis (total leukocyte count = 15.4 × 10^9/L) and blood culture with growth of group B streptococci which resolved with use of cefoxitin (2 g IV every 6 hours) and clindamycin (300 mg every 8 hours). Parenteral treatment persisted until the patientâ??s temperature stayed below 37.8 â?? (100 °F) for 24 hours, the patient was free of pain, and the leukocyte count was returning to normal [17].

Another patient in group B (without cervical dilatation) developed postpartum endometritis that was manifested by fever and abdominal pain. The diagnosis was confirmed by a complete blood picture showing leukocytosis(total leukocyte count =18.7 × 10^9/L) and blood culture with the growth of Staphylococcus. Ultrasound revealed pelvic collection of fluid. Exploration was done with drainage of pelvic abscess. Patient improvement was achieved by postoperative administration of Ceftriaxone (1 g IV every 24 hours), Doxycycline (100 mg IV every 12 hours) and Metronidazole (500 mg IV every 12 hours). Parenteral therapy continued until the patient's temperature has remained lower than 37.8 â?? (100°F) for 24 hours, the patient is pain free, and the leukocyte count is normalizing [17].

We found no significant difference between the two groups in terms of developing postpartum endometritis, which aligns with most previous studies on mechanical cervical dilatation's effect on reducing this risk.

Ahmed and colleagues carried out a clinical trial to assess the impact of routine cervical dilatation during elective cesarean sections on maternal morbidity involving 131 patients. Among these 131 participants, 67 received cervical dilation while 64 acted as the control group. No significant differences were observed in the occurrence of fever between the two groups. Only two patients from the cervical dilation group and one from the control group experienced postoperative fever. They concluded that performing intraoperative cervical dilatation during elective cesarean sections did not lower the risk of postoperative maternal fever [8].

Koifman and colleagues performed a retrospective study involving 666 patients who had elective cesarean sections (CS). Of the 666 elective CS cases, 348 involved standard cervical dilatation. No notable differences were observed between the cervical dilatation group and the comparison group concerning postpartum febrile morbidity. They concluded that routine cervical dilatation during elective CS does not decrease postoperative morbidity[18].

Tosun and associates conducted a randomized trial examining the need for cervical dilation in elective CS with 150 patients. The two groups were similar in terms of demographic and clinical characteristics. Febrile morbidity occurred in one patient from the dilated group. Endometritis was not reported in either group during the postpartum period. They concluded that cervical dilatation appears to be an unnecessary procedure during cesarean sections[19].

Liabsuetrakul, et al. included three trials with a total of 735 women undergoing elective caesarean section. Of these women, 338 underwent intraoperative cervical dilatation with a double-gloved index digit inserted into the cervical canal to dilate, and 397 did not undergo intraoperative cervical dilatation. The incidence of febrile morbidity in women after cervical dilatation during non-labor caesarean sections was similar to those who did not undergo the procedure. There were no significant differences in endometritis or infectious morbidity, leading to the conclusion that mechanical cervical dilatation does not reduce postoperative morbidity [4].

Sakinci, et al. study included 199 patients: 102 in the non-dilated group and 97 in the cervical dilatation group. The rate of puerperal fever was found to be similar across both groups. Ultimately, he concluded that intra-operative cervical dilatation does not appear to provide any advantage concerning puerperal fever [20].

Kirscht et al. included 447 women undergoing elective cesarean sections in a trial comparing cervical dilatation versus no dilatation, assessing postpartum hemorrhage, infectious complications, blood loss, and operating time. In this study, cervical dilatation was carried out in 205 women (dilatation group) while it was not performed in 242 women (no dilation group). The rates of infectious complications did not differ between the two groups. They concluded that performing cervical dilatation during cesarean section did not affect the risk of infectious complications (puerperal fever, endometritis) compared to not performing dilatation[7].

Dawood and colleagues enrolled 422 women who had elective cesarean sections in their research to evaluate the effectiveness of transabdominal mechanical cervical dilatation in reducing postpartum endometritis. There was no significant variation in the endometritis rates between the two groups. The group without cervical dilatation experienced a higher incidence of febrile morbidity than the group with cervical dilatation. In terms of infectious morbidity, no significant differences were found regarding endometritis between the two groups. They hypothesized that the increased febrile morbidity in the non-dilated cervix group was due to retained blood in the lower segment of the uterus[21].

The latest research conducted by Uzun involved 95 women, comprising 48 (50.5%) in the cervical dilatation group and 47 (49.5%) in the non-cervical dilatation group. A wound infection was observed in one case in each group. No significant difference in fever was noted. They concluded that there is a lack of sufficient data regarding cervical dilatation to lower postoperative morbidity during cesarean sections[22].

In our study, six patients in group A (with cervical dilatation) developed wound sepsis. Four patients presented with seromas; three were small and resolved spontaneously, while one large seroma required drainage with a syringe needle. One patient developed wound cellulitis, which resolved with repeated dressing and topical antibiotics (bivatracin). One patient suffered from a wound breakdown, which was treated by repeated dressing followed by a secondary suture.

On the other hand, four patients in group B (without cervical dilatation) developed wound sepsis. Three patients in the form of seroma that were small and resolved spontaneous with no need for further intervention. One patient developed wound abscess that was drained surgically.

However, there are many factors (other than infection) may affect wound sepsis eg: Age of Patient, personal hygiene, Chronic Diseases, Poor Nutrition, Lack of Hydration, Poor Blood Circulation, Obesity, Edema and some special habits as smoking.

We concluded that there was no statistically significant between both groups regarding wound sepsis.

In Ahmed et al.'s study, none of the patients exhibited symptoms of wound infection. There was no notable difference in the incidence of wound infection observed between the two groups. They concluded that cervical dilatation during elective cesarean sections did not lower the risk of wound infection[8].

The research conducted by Koifman et al. found no significant difference in wound infection rates between the cervical dilatation group and the comparison group. They determined that routine cervical dilatation during elective cesarean sections does not diminish postoperative morbidity[18].

Liabsuetrakul et al. reported no significant differences in wound infection occurrences. They concluded that there was a lack of sufficient evidence to suggest that mechanical cervical dilatation at non-labor cesarean sections reduces postoperative morbidity[4].

According to the study by Kirscht et al., there was no divergence in wound sepsis rates between the two groups. They concluded that cervical dilatation during cesarean sections, when compared to no dilatation, did not affect the risk of wound infection[7].

In the study conducted by Dawood et al., there was no significant difference observed in the incidence of wound infections[21].

Uzun reported one case of wound infection in each group, showing no notable difference in infection rates. They concluded that there is inadequate data regarding cervical dilatation's impact on reducing postoperative complications during cesarean sections[22].

In our research, there was no statistically significant difference noted between the two groups concerning the decrease in hemoglobin levels preoperatively and postoperatively, which aligns with most previous studies examining the effect of mechanical cervical dilatation on hemoglobin changes during this timeframe.

Ahmed et al. study, a hemoglobin drop of more than 0.5 g/dL was noted in 27 and 26 patients in the cervical dilation and the no dilation groups, respectively which were nonsignificant. They concluded that intraoperative cervical dilatation during elective cesarean section did not affect hemoglobin drop between preoperative and postoperative[8].

In the study by Tosun et al., the degree of hemoglobin reduction was similar across both groups. There was no significant statistical difference in hemoglobin levels between the preoperative and postoperative stages for either group. They concluded that intraoperative cervical dilation during elective cesarean sections did not impact the change in hemoglobin between preoperative and postoperative measurements[19]

The research conducted by Liabsuetrakul et al. indicated that the incidence of hemoglobin concentrations in the postoperative period for women undergoing intraoperative cervical dilation was not markedly different from those who did not undergo dilation. There was no significant difference in the changes in hemoglobin levels or hematocrit levels during the postoperative period. They concluded that there was inadequate evidence supporting the mechanical dilation of the cervix during non-labor cesarean sections to mitigate hemoglobin reduction between preoperative and postoperative periods[4].

Sakinci's research found that hemoglobin levels were comparable between the two groups. Ultimately, he concluded that intraoperative cervical dilation does not appear to provide any advantages concerning changes in hemoglobin concentrations[20].

Kirscht et al. examined the effects of cervical dilation versus no dilation during cesarean sections concerning blood loss, specifically the requirement for blood transfusions or changes in hemoglobin levels. They found no substantial difference in blood loss between the two groups. They concluded that cervical dilation during cesarean sections did not affect blood loss, the need for transfusions, or changes in hemoglobin levels[7].

However, a study by Uzun did not support our conclusion as he noticed that the differences between the median values of both groups were compared (preoperative and postoperative hemoglobin values of the individuals in both groups), hemoglobin and hematocrit values were found to be significantly higher in the group without dilatations compared to the group with dilatations. They concluded that the median of difference of hemoglobin and hematocrit values was significantly higher in the cervical dilatation group[22].

In our study, there was no reduction in hospital stay in days between dilatation group and non-dilatation group. We concluded that mechanical cervical dilation during elective CS is not associated with reduction of hospital stay in days. However, there are many factors may affect postoperative hospital stay eg: maternal age, parity, weight, general condition, prior obstetrical history, prior medical history (hypertension, diabetes â?¦. Etc.), bowel motility, pain tolerance, easy ambulation, prior surgical history and breastfeeding.

Sakinciâ??s study did not support our conclusion as he noticed that group with cervical dilatation needed shorter hospital stay than the other group. He concluded that mechanical cervical dilation during elective CS is associated with reduction of postoperative hospital stay in days[20].

Dawood, et al. also did not support our conclusion as he noticed that the duration of hospital stay was signiï¬cantly higher in the no cervical dilatation group. He concluded that mechanical cervical dilation during elective CS is associated with reduction of postoperative hospital stay in days [21].

In our study, none of the patients developed cervical injury during mechanical dilatation of the cervix. There was no previous studies assessed the incidence of cervical injury during mechanical cervical dilatation of cervix.

Conclusion

Dilatation of the cervix during cesarean section compared with no dilatation of the cervix did not influence the risk of postpartum endometritis, wound infection, drop between preoperative and postoperative hemoglobin, and hospital stay in days.

Recommendations

It is recommended that further research is needed using a larger sample size or retrograde follow-up of postpartum endometritis patients to see if they underwent transabdominal mechanical dilatation of the cervix during their elective CS or not.

References

- Haas DM, Morgan S, Contreras K, et al. Vaginal preparation with antiseptic solution before cesarean section for preventing postoperative infections. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2020(4).

- Mackeen AD, Packard RE, Ota E, et al. Antibiotic regimens for postpartum endometritis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015(2).

- Guengoerduek K, Yildirim G, Ark C. Is routine cervical dilatation necessary during elective caesarean section? A randomised controlled trial. Aust N Z J Obstet Gynaecol. 2009;49(3):263-267.

- Liabsuetrakul T, Peeyananjarassri K. Mechanical dilatation of the cervix at non‐labour caesarean section for reducing postoperative morbidity. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2011(11).

- Dodd JM, Anderson ER, Gates S, et al. Surgical techniques for uterine incision and uterine closure at the time of caesarean section. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014(7).

- Osemwenkha A, Olagbuji B, Ezeanochie M. A comparative study on routine cervical dilatation at elective cesarean section. Afr J Med Health Sci. 2013;12(2):76.

- Kirscht J, Weiss C, Nickol J, et al. Dilatation or no dilatation of the cervix during cesarean section (Dondi Trial): A randomized controlled trial. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2017;295:39-43.

- Ahmed B, Abu Nahia F, Abushama M. Routine cervical dilatation during elective cesarean section and its influence on maternal morbidity: A randomized controlled study. J Perinat Med. 2005:33(6): 510-513.

- Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (RCOG). Care of women presenting with suspected preterm prelabour rupture of membranes from 24+0 Weeks of Gestation. (Green-top guideline; no. 73). 2015.

- Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (RCOG). Prevention and management of postpartum hemorrhage (Green-top Guideline; No. 52). 2016.

- No GT. Blood transfusion in obstetrics. Obst Gyne J. 2015 May;5:6-11.

- Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists (RCOG) (2012) Bacterial sepsis following pregnancy. (Green-top guideline; no. 64b). 2012.

- No GT. Prevention and management of postpartum haemorrhage. BJOG. 2016;124:e106-e149.

- National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) (2021) Caesarean section Clinical guideline [CG194]. 2021.

- Altman R, Bosch B, Brune K, et al. Advances in NSAID development: Evolution of diclofenac products using pharmaceutical technology. Drugs. 2015;75:859-877.

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) Committee Opinion No. 750. Perioperative pathways: Enhanced recovery after surgery. 132:e120-30. 2018.

- Bennett JE, Dolin R, Blaser MJ, et al. “Principles and practice of infectious diseases: 2-volume set. Elsevier Health Sciences; 9th Edition”.

- Koifman A, Harlev A, Sheiner E, et al. Routine cervical dilatation during elective cesarean delivery–Is it really necessary?. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2009;22(7):608-611.

- Tosun M, Sakinci M, Çelik H, et al. A randomized controlled study investigating the necessity of routine cervical dilatation during elective cesarean section. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2011;284:85-89.

- Sakinci M, Kuru O, Olgan S, et al. Dilatation of the cervix at non-labour caesarean section: Does it improve the patients’ perception of pain post-operatively?. J Obstet Gynaecol. 2015;35(7):681-4.

- Dawood AS, Elgergawy A, Elhalwagy A, et al. The impact of mechanical cervical dilatation during elective cesarean section on postpartum scar integrity: A randomized double-blind clinical trial. Int J Womens Health. 2019 Jan 10:23-29.

- Uzun A. Effects of cervical dilatation during cesarean section on postpartum process. Anatol J Fam Med. 2020;3(3).

Google Scholar, Crossref, Indexed at

Google Scholar, Crossref, Indexed at

Google Scholar, Crossref, Indexed at

Google Scholar, Crossref, Indexed at

Google Scholar, Crossref, Indexed at

Google Scholar, Crossref, Indexed at

Google Scholar, Crossref, Indexed at

Google Scholar, Crossref, Indexed at

Google Scholar, Crossref, Indexed at

Google Scholar, Crossref, Indexed at

Google Scholar, Crossref, Indexed at

Google Scholar, Crossref, Indexed at

Author Info

Nadim A, Eissa Y*, El Sayed M and Maaty ACopyright:This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.