Research - (2023) Volume 18, Issue 1

Correlation of clinical characteristics and outcomes of patients admitted to obstetric ICU with micro-angiopathic haemolytic anaemia (MAHA): A 5-year retrospective analysis

Heba Abd El KarimReceived: 05-Aug-2022, Manuscript No. gpmp-22-71318; Editor assigned: 06-Aug-2022, Pre QC No. P-71318; Reviewed: 19-Nov-2022, QC No. Q-71318; Revised: 03-Dec-2022, Manuscript No. R-71318; Published: 29-Mar-2023

Abstract

Aim: The purpose of this study was to review all obstetric patients admitted to ICU in Ain Shams University Maternity Hospital over 5-years period due to thrombotic microangiopathies (SPET, HELLP, HUS, AFLP, TTP), thereby to analyze the frequency, clinical characteristics, interventions, treatment, and maternal and neonatal outcomes

Patients and methods: We reviewed medical charts of above-mentioned patients.

Results: The patients’ age was 30.22 ± 6.24 years, with parity of 3.3±1.16. Most were admitted at postpartum period, and ICU stay was 2.8 ± 1.64 days. Hypertension (24%) and DM (16%) were the most common co-morbidities. The neonatal weight was 2.35 ± 0.82, and the incidence of IUGR was 2.7%. Neonatal weight from AFLP was significantly low. Maternal death occurred in 28 (4.7%) due to HELLP (n=8), HUS (4), undiagnosed (4), AFLP (4), SPET (4), eclampsia (4). Death was due to multi-organ failure, pulmonary emboli, DIC, cerebral hemorrhage and stroke. Regarding the complications, 12 (2%) suffered with eclampsia, 28 (4.7%) with accidental hemorrhage, and 8 (1.3%) with renal failure. The incidence of antepartum Hemorrhage was higher among patients with HUS-TTP than those with PE-Eclampsia-HELLP by 33% for HUS-TTP versus 3.5% for PE-Eclampsia-HELLP. Thus, pregnant patients with TTP-HUS had a greater risk of maternal complications than those with PE-Eclampsia-HELLP.

Conclusion: Some demographic, clinical, and laboratory characteristics could correlate with specific types of MAHA. Physicians should be aware of this.

Keywords

Micro-angiopathic haemolytic anaemia; Obstetric ICU; Preeclamptic toxemia

Introduction

Microangiopathic Hemolytic Anemia (MAHA) refers to anemia caused by destruction of erythrocytes due to physical shearing as a result of passage through small vessels occluded by systemic [1]. Thrombotic microangiopathies (TMA) are a group of related disorders that are characterized by thrombosis of the microvasculature and associated organ dysfunction, and encompass congenital, acquired, and infectious etiologies [1,2].

The primary diagnostic challenge is the differentiation from acute fatty liver of pregnancy (AFLP), preeclampsia or eclampsia and HELLP (hemolysis, elevated liver enzymes, low platelets). Features of PET and HELLP may be the initial presentation prior to the clinical picture evolving and subsequent diagnosis of TTP or HUS, thus further complicating the diagnostic process. Antiphospholipid syndrome (APS), systemic lupus erythematosus and disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC) may also present with MAHA picture in association with thrombocytopenia [3].

An important issue for the evaluation of a pregnant or postpartum woman with severe MAHA and thrombocytopenia is to appreciate the relative incidence of PE/HELLP syndrome, TTP, HUS, and AFLP. PE/HELLP syndrome is much more common than either TTP or HUS [2].

Although pregnancy-associated TTP most commonly presents in the third trimester or postpartum period, TTP remains the most likely diagnosis of a TMA presenting in the first trimester. Treatment of MAHA and TMA in pregnancy is based on maternal factors, although fetal wellbeing and viability will dictate the timing of delivery. Presentation of a TMA requires careful review of clinical features and laboratory parameters to aid in differential diagnosis. The primary decision is whether delivery will be associated with remission of the TMA (as in PET or HELLP), or whether plasma exchange (PEX) should be urgently instigated as recovery following delivery is unlikely and there is a risk of multi-organ dysfunction/death [4].

Patients and Methods

Type of Study: Retrospective study.

Study Setting: The study was conducted at Ain Shams University Maternity Hospital, Obstetrics ICU.

Study Population: The study population comprises all women admitted to obstetric ICU at Ain Shams University Maternity Hospital, during the last 5 year, with MAHA variants including SPET, HELLP, TTP, AFLP, HUS.

Inclusion criteria:

All obstetric patients admitted to obstetric ICU due to microangiopathic anemia variants which include:

1. Severe preeclampsia (SPET).

2. HELLP syndrome.

3. Acute fatty liver of pregnancy (AFLP).

4. Thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpra(TTP).

5. Heamolytic ureamic syndrome (HUS).

Exclusion criteria:

• Patients admitted to obstetric ICU unit due to other causes

Methods:

This is a retrospective study of consecutive obstetric patients admitted to the ICU of Ain Shams maternity Hospital over a 5-year period from January 2013 to December 2017. Our ICU is a 12 bed closed unit, which admits more than 1000 patients annually.

Patients admitted within the above period was identified using the paper filed database of the Medical Records Department. The admission books of our ICU will also utilized, so as not to miss any eligible patient. The patient records will then be screened to ensure that when admitted, they were pregnant or within 42 days of termination of pregnancy.

Each patient record was reviewed in detail. The data that was retrieved for analysis include demographics (age, smoking and drinking status), comorbidities, obstetric features (parity, detailed antepartum history about current and previous pregnancies as number of abortions, ectopic, living children, still birth, history of accidental hge, gestational HTN or DM, weeks of gestation, antenatal abnormalities as IUGR, macrosomia, oligohydramnios, polyhydraminos, mode of delivery, vital signs including pulse, blood pressure, temperature, oxygen saturation, urine output, and Glasgow Coma Scale score on admission, lowest score during admission and discharge score).

Lab investigations and radiological investigations done to the patients at the time of admission and during the admission including, urinalysis, FBC and blood film, reticulocytes, schistocytes, clotting screen, urea and electrolytes, liver function tests, lactate dehydrogenase, FDPs, fibrinogen level, D-dimer, assessment of fetal wellbeing (age, weight, APGAR score at 1 and 5 minutes from delivery, and fetal outcome.

Results

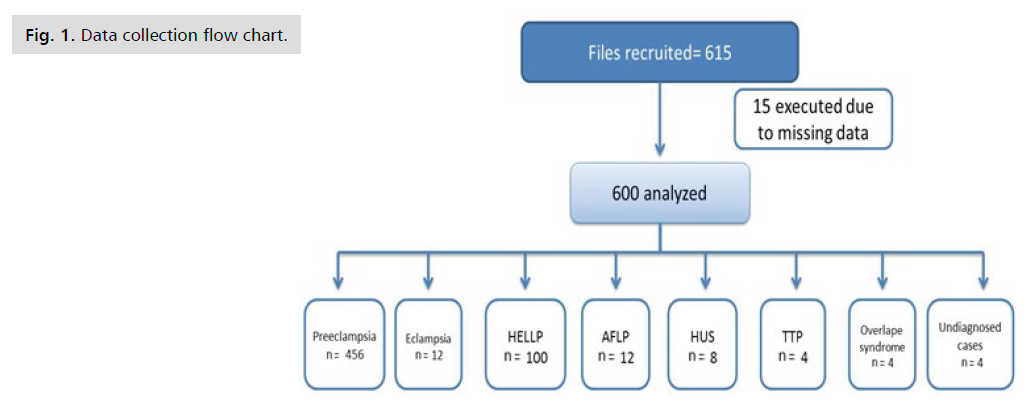

Our obstetric ICU admit more than 1000 patients annually. This study was a retrospective record based study that included 615 files from the year 2013 to the year 2017. Fifteen files were excluded due to missing data and lack of registration sufficiency. The data collection process is shown in fig. 1.

Fig 1. Data collection flow chart.

Descriptive analysis:

Demographic data of the population of the studied files are represented in Tab. 1. Tab. 2. shows the obstetric history represented by number of parity and abortions in the studied population. Fifty nine percent of the women of the included files were multiparous (para 1-5), while 40.6% were nulliparous. Tab. 3. shows prevalence of relevant medical diseases in the study population. Twenty four percent of the patients were hypertensive, 16% diabetic, 12% had autoimmune disease mostly was systemic lupus erythematous. Tab. 4. shows obstetric complications of the study population. Gestational hypertension was more common than gestational diabetes, antepartum haemorrhage occurred in about 4.7% of the study population. Tab. 5. shows mode of delivery of the study population. Regarding operative complications and mode of delivery 92.7% of the patients of the studied files were delivered by caesarean section, 24% delivered by normal vaginal delivery. Tab. 6. & 7. Shows ICU data and different lab investigations collected from the files of the studied population. Mean systolic B/P at the time of admission was 176.00 ± 21.71 systolic and diastolic B/P 105.60 ± 13.75. Mean of the lowest Glasgow coma score was 11.11 ± 1.54 and at discharge which refers to either improvement of the patient or death was 13.40 ± 2.36. The average length of ICU stay was 2 days. Range from 1 day to 17 days.

| Variables | No.=600 | |

|---|---|---|

| Age | Mean ± SD | 30.27 ± 6.25 |

| Range | 20–40 | |

| Special habit | No | 584 (97.3%) |

| Smoker | 16 (2.7%) | |

Tab. 1. Demographic data.

| Variables | No.=600 | |

|---|---|---|

| Parity | PO (previous miscarriage) | 80 (13.3%) |

| PG | 164 (27.3%) | |

| P(1-3) | 288 (48.0%) | |

| P(4-5) | 68 (11.3%) | |

| Abortion | Median (IQR) | 3.00 (2-4) |

| Range | 1.00–10.00 | |

Tab. 2. Obstetric history.

| Variables | No.=600 | |

|---|---|---|

| Hypertension. | No | 456 (76.0%) |

| Yes | 144 (24.0%) | |

| Diabetes mellitus. | No | 504 (84.0%) |

| Yes | 96 (16.0%) | |

| Auto immune disease | No | 588 (98.0%) |

| SLE | 12 (2.0%) | |

| Gestational Age | Mean ± SD | 33.42 ± 3.98 |

| Range | 22.2–40 | |

Tab. 3. Prevalence of relevant medical diseases in the whole study population.

| Variables | No. | % | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gestational diabetes | No | 572 | 95.3% |

| Yes | 28 | 4.7% | |

| Gestational hypertension | No | 564 | 94.0% |

| Yes | 36 | 6.0% | |

| Ante partum haemorrhage | No | 568 | 95.3% |

| Yes | 28 | 4.7% | |

Tab. 4. Obstetric complications.

| Variables | No. | % | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mode OF Delivery | LSCS | 556 | 92.7% |

| NVD | 24 | 4.0% | |

| Suction evacuation | 8 | 1.3% | |

| CS Hysterectomy | 4 | 0.7% | |

| D & C | 4 | 0.7% | |

| Hystrotomy | 4 | 0.7% | |

Tab. 5. Mode of delivery.

| Variables | No.=600 | |

|---|---|---|

| Highest ICU PULSE | Mean ± SD | 97.05 ± 9.05 |

| Range | 80–120 | |

| Highest ICU Systolic Blood pressure. |

Mean ± SD | 176.00 ± 21.71 |

| Range | 110–220 | |

| Highest ICU Diastolic Blood pressure |

Mean ± SD | 105.60 ± 13.75 |

| Range | 70–160 | |

| Highest ICU Temperature. | Mean ± SD | 37.00 ± 0.36 |

| Range | 36.5–39 | |

| Lowest ICU Urine output/hour |

Mean ± SD | 59.70 ± 15.84 |

| Range | 40–110 | |

| ICU Glasgow base | Mean ± SD | 11.37 ± 1.87 |

| Range | 3–14 | |

| Glasgow lowest | Mean ± SD | 11.11 ± 1.54 |

| Range | 3–14 | |

| Glasgow discharge* | Mean ± SD | 13.40 ± 2.36 |

| Range | 3–15 | |

| Duration of ICU stay (day) | Median (IQR) | 2 (1-2) 0–17 |

| Range | ||

Tab. 6. ICU data.

| Variables | No.=600 | |

|---|---|---|

| Lowest Hb | Mean ± SD | 9.08 ± 0.97 |

| Range | 6.5–11 | |

| Hb at discharge | Mean ± SD | 9.97 ± 0.96 |

| Range | 6–11.9 | |

| TLC | Mean ± SD | 11.43 ± 4.02 |

| Range | 5.8–22.5 | |

| Lowest PLT | Mean ± SD | 173.79 ± 72.87 |

| Range | 47–401 | |

| PLT at discharge | Mean ± SD | 197.37 ± 55.97 |

| Range | 23–389 | |

| Albumin in urine at admission | ALB nil | 16 (2.7%) |

| ALB + | 64 (10.7%) | |

| ALB ++ | 268 (45.0%) | |

| ALB +++ | 232 (38.9%) | |

| ALB trace | 16 (2.7%) | |

| Highest Clotting INR | Mean ± SD | 1.01 ± 0.15 |

| Range | 0.7–2.24 | |

| Highest Urea | Median (IQR) | 40 (32-50) |

| Range | 14–300 | |

| Highest Serum Creatnine | Median (IQR) | 0.9 (0.8–10.3) |

| Range | 0.5–10.3 | |

| Serum Creatnine at discharge | Median (IQR) | 0.9 (0.9–1) |

| Range | 0.6–8 | |

| Highest ALT | Median (IQR) | 44 (22-90) |

| Range | 9–340 | |

| ALT at discharge | Median (IQR) | 26 (20–34) |

| Range | 11–410 | |

| Highest AST | Median (IQR) | 29 (17-89) |

| Range | 7–410 | |

| AST at discharge | Median (IQR) | 26.5 (22–33) |

| Range | 7–433 | |

| Highest LDH | Median (IQR) | 507 (275.5-667) |

| Range | 180–5268 | |

Tab. 7. Lab investigations.

Lab investigations:

Mean of Hb at the time of admission was 9.08 ± 0.97, at time of discharge 9.97 ± 0.96. Mean of PLT at time of admission 173.79 ± 72.87 at time of discharge 197.37 ± 55.97. Mean of highest serum creatnine was 0.9 (0.8 – 10.3) and at discharge was 0.9 (0.9 – 1). The final diagnosis and maternal outcome of the women of the studied files are represented in table 8. Unfortunately there were 28 deaths among study population. The most common diagnosis was SPET (76%) followed by HELLP syndrome (16.7), while the lowest were TTP, overlap syndrome & undiagnosed MAHA was reported in 0.7% of files. The neonatal outcome of the studied files is represented in Tab. 8. Percentage of live birth was 92.4 among them 4.8% were twins. The mean of neonatal weight was 2.35 ± 0.82, with 8% of them was IUFD 2.7% was IUGR as shown (Tab. 9.). Tab. 10. Shows that the total number of neonatal deaths is 48 case, 44 cases of them were born to mothers with PE-Eclampsia-HEELP and 4 of them with AFLP. Their gestational ages ranges from 22week to 39week and mean 29 week with neonatal weight ranges from 0.7 kg to 3.2 kg and Mean 2.11 kg.

| Variables | No. | % | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Outcome | Death | 28 | 4.7% |

| Recovery | 572 | 95.3% | |

| Final diagnosis | SPET | 456 | 76.0% |

| HELLP | 100 | 16.7% | |

| AFLP | 12 | 2.0% | |

| ECLAMPSIA | 12 | 2.0% | |

| HUS | 8 | 1.3% | |

| TTP | 4 | 0.7% | |

| Overlap syndrome | 4 | 0.7% | |

| Undiagnosed MAHA | 4 | 0.7% | |

Tab. 8. Final diagnosis and maternal outcome.

| Variables | No.=600 | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Neo Weight (Kg) | Mean ± SD | 2.35 ± 0.82 | |

| Range | 0.5–4 | ||

| APGAR score 1 min | Median (IQR) | 7 (6-8) | |

| Range | 4–8 | ||

| APGAR score 5min | Median (IQR) | 9 (8-9) | |

| Range | 7–9 | ||

| FETAL ANOMALY | No | 520 | 86.7% |

| IUFD | 48 | 8.0% | |

| IUGR | 16 | 2.7% | |

| Invietable abortion | 4 | 0.7% | |

| Lost diastolic flow | 8 | 1.3% | |

| Twin to twin transfusion syndrome | 4 | 0.7% | |

| Number of live birth | No | 48 | 8.4% |

| One | 504 | 86.8% | |

| Two | 28 | 4.8% | |

Tab. 9. Neonatal outcome.

| IUFD cases | No.=48 | |

|---|---|---|

| Gestational age | Mean ± SD | 29.42 ± 4.60 |

| Range | 22.2–39.3 | |

| Neonatal weight (Kg) | Mean ± SD | 2.11 ± 0.91 |

| Range | 0.7–3.2 | |

Tab. 10. IUFD cases.

Comparative analysis

Comparison between study cases regarding demographic data shown in Tab. 11. The previous table shows that there was statistically significant difference found between 4 groups of diseases in present study regarding age, AFLP presents more frequent in older age females while TTP/HUS were more in younger age females. Regarding smoking there was no statistically significant difference found between 4 groups of diseases in present study which means smoking was not risk factor for any of the diseases included in the study. Comparison between study cases regarding parity and number of abortions shown in Tab. 12. This table shows that there was statistically significant difference found between 4 groups of diseases in present study regarding number of parity and abortion, AFLP has higher incidence among primigravidas more than multiparas woman, while overlape syndrome and undiagnosed MAHA was higher among multiparus women, also TTP/ HUS was higher among primigravidas than multiparus. Comparison between study cases regarding different medical conditions found among study population shown in Tab. 13. The previous table shows that there was statistically significant difference found between 4 groups of diseases in present study regarding different medical conditions found in the study population, chronic HTN was found in patients with PE-Eclampsia-HELLP more frequent than patients with AFLP – HUS –TTP, also DM is a risk factor for developing PE-Eclampsia-HELLP but not a risk factor for HUS-TTP among study population. Comparison between study cases regarding different obstetric problems shown in Tab. 14. The previous table shows that there was no statistically significant difference found between 4 groups of diseases in present study regarding gestational DM and gestational HTN, However there was statistically significant difference found between 4 groups of diseases in present study regarding the incidence of antepartum Hge, antepartum Hge was higher among patients with HUS-TTP & AFLP than patients with PE-ECLAMPSIA-HELLP. Comparison between study cases regarding mode of delivery shown in Tab. 15.

| Variables | PE-Eclampsia- HELLP |

HUS/TTP | AFLP | Overlap syndrome |

Test value | P-value | Sig. | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No.=568 | No.=12 | No.=12 | No.=8 | |||||

| Age | Mean ± SD | 30.22 ± 6.24 | 25.67 ± 4.70 | 38.50 ± 0.54 | 32.50 ± 2.67 | 7.383• | 0.000 | HS |

| Range | 20–40 | 22–32 | 38–39 | 30–35 | ||||

| special habit | No | 552 (97.2%) | 12 (100.0%) | 12 (100.0%) | 8 (100.0%) | 0.805* | 0.848 | NS |

| Smoker | 16 (2.8%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | ||||

Tab. 11. Comparison between study cases regarding demographic data.

| Variables | PE-Eclampsia-HELLP | HUS/TTP | AFLP | Overlap syndrome | Test value | P-value | Sig. | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. =568 | No. =8 | No. =12 | No. =8 | |||||

| Parity | PO (previous miscarriage) | 72 (12.6%) | 0 (0.0%) | 4 (33.3%) | 0 (0.0%) | 38.661* | 0.000 | HS |

| PG | 152 (26.6%) | 8 (66.7%) | 8 (66.7%) | 0 (0.0%) | ||||

| P(1-3) | 280 (49.0%) | 4 (33.3%) | 0 (0.0%) | 4 (50.0%) | ||||

| P(4-5) | 64 (11.2%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 4 (50.0%) | ||||

| Abortion | Median(IQR) | 3.00 (2-4) | - | 3.00 (3-3) | 1.00 (1-1) | -2.809‡ | 0.005 | HS |

| Range | 1.00–10.00 | - | 3.00–3.00 | 1.00–1.00 | ||||

Tab. 12. Comparison between study cases regarding parity and number of abortions.

| Variables | PE-Eclampsia-HELLP | HUS/TTP | AFLP | Overlap syndrome | Test value | P-value | Sig. | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No.=568 | No.=12 | No.=12 | No.=8 | |||||

| Hypertension | No | 428 (75.3%) | 12 (100.0%) | 12 (100.0%) | 4 (50.0%) | 9.352* | 0.025 | S |

| Yes | 140 (24.5%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 4 (50.0%) | ||||

| Diabetes mellitus | No | 480 (84.5%) | 12 (100.0%) | 8 (66.6%) | 4 (50.0%) | 16.209* | 0.001 | HS |

| Yes | 88 (15.4%) | 0 (0.0%) | 4 (33.3%) | 4 (50.0%) | ||||

| Auto immune disease | No | 556 (97.8%) | 12 (100.0%) | 12 (100.0%) | 8 (100.0%) | 0.599* | 0.897 | NS |

| SLE | 12 (2.1%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | ||||

Tab. 13. Comparison between study cases regarding different medical conditions found among study population.

| Variables | PE-Eclampsia-HELLP | HUS/TTP | AFLP | Overlap syndrome | Test value | P-value | Sig. | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. | % | No. | % | No. | % | No. | % | |||||

| G DM | No | 540 | 95% | 12 | 100.0% | 12 | 100.0% | 8 | 100.0% | 1.438 | 0.697 | NS |

| Yes | 28 | 4.9% | 0 | 0.0% | 0 | 0.0% | 0 | 0.0% | ||||

| GHTN | No | 532 | 93.6% | 12 | 100.0% | 12 | 100.0% | 8 | 100.0% | 1.875 | 0.599 | NS |

| Yes | 36 | 6.3% | 0 | 0.0% | 0 | 0.0% | 0 | 0.0% | ||||

| Ante partum He | No | 548 | 96.5% | 8 | 66.7% | 12 | 100.0% | 4 | 50.0% | 60.799 | 0.000 | HS |

| Yes | 20 | 3.5% | 4 | 33.3% | 0 | 0.0% | 4 | 50.0% | ||||

Tab. 14. Comparison between study cases regarding different obstetric problems.

| Variables | PE-Eclampsia-HELLP | HUS/TTP | AFLP | Overlap syndrome | Test value | P-value | Sig. | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. | % | No. | % | No. | % | No. | % | |||||

| M OF DELIVERY | LSCS | 528 | 92.9% | 12 | 100.0% | 12 | 100.0% | 4 | 50.0% | 299.653 | 0.000 | HS |

| NVD | 24 | 4.2% | 0 | 0.0% | 0 | 0.0% | 0 | 0.0% | ||||

| Suction evacuation | 8 | 1.4% | 0 | 0.0% | 0 | 0.0% | 0 | 0.0% | ||||

| CS Hysterectomy | 0 | 0.0% | 0 | 0.0% | 0 | 0.0% | 4 | 50.0% | ||||

| D & C | 4 | 0.7% | 0 | 0.0% | 0 | 0.0% | 0 | 0.0% | ||||

| Hystrotomy | 4 | 0.7% | 0 | 0.0% | 0 | 0.0% | 0 | 0.0% | ||||

Tab. 15. Comparison between study cases regarding mode of delivery.

The previous table shows that there was high statistically significant difference found between 4 groups of diseases in present study regarding mode of delivery, patients with AFLP,HUS and TTP all delivered by emergency CS, CS hysterectomy was done in 4 cases diagnosed with overlap syndrome, NVD only found in 24 cases all of them preeclampsia, eclampsia and HELLP syndrome. Comparison between study cases regarding neonatal outcome shown in Tab. 16.

| Variables | PE-Eclampsia- HELLP |

HUS/TTP | AFLP | Overlap syndrome |

Test value | P-value | Sig. | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No.=568 | No.=12 | No.=12 | No.=8 | |||||

| NEO WT (Kg) | Mean ± SD | 2.36 ± 0.81 | 2.73 ± 0.94 | 1.00 ± 0.11 | 3.00 ± 0.00 | 9.287• | 0.000 | HS |

| Range | 0.5–4 | 2–4 | 0.9–1.1 | 3–3 | ||||

| APGAR score 1 min | Median (IQR) | 7 (6-8) | 7 (7-8) | 6 (6-6) | 8 (8-8) | 15.368‡ | 0.002 | HS |

| Range | 4–8 | 7–8 | 6–6 | 8–8 | ||||

| APGAR score 5min | Median (IQR) | 9 (8-9) | 9 (8-9) | 7 (7-7) | 9 (9-9) | 15.837‡ | 0.001 | HS |

| Range | 7–9 | 8–9 | 7–7 | 9–9 | ||||

| FETAL ANOMALY | No | 492 (86.6%) | 12 (100.0%) | 8 (66.6%) | 8 (100.0%) | 22.526 | 0.095 | NS |

| IUFD | 44 (7.7%) | 0 (0.0%) | 4 (33.3%) | 0 (0.0%) | ||||

| IUGR | 16 (2.8%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | ||||

| Inevitable abortion | 4 (0.7%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | ||||

| Lost diastolic flow | 8 (1.4%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | ||||

| Twin to twin transfusion syndrome |

4 (0.7%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | ||||

| Number of live birth | No | 40 (7.2%) | 0 (0.0%) | 4 (50.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 3.080 | 0.001 | HS |

| One | 488 (87.8%) | 12 (100.0%) | 4 (50.0%) | 4 (100.0%) | ||||

| Two | 28 (5.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | ||||

| Gestational Age |

Mean ± SD | 33.49 ± 3.91 | 34.40 ± 4.36 | 29.30 ± 0.11 | 30.7 ± 6.84 | 4.486 | 0.004 | HS |

| Range | 22.2–40 | 30–40 | 29.2–29.4 | 24.3–37.1 | ||||

Tab. 16. Comparison between study cases regarding neonatal outcome.

The previous table shows that there was high statistically significant difference found between 4 groups of diseases in present study regarding neonatal outcome, IUFD was more in cases with AFLP and Preeclampsia-eclampsia-HELLP syndrome, APGAR score was lowest in AFLP, neonatal weight was significantly low among patients with AFLP. There was also high statistically significant difference found between 4 groups of diseases in present study regarding APGAR score but this difference of no clinical significance. Regarding gestational age there was high statistically significant difference between four groups of diseases in our study, AFLP and overlap syndrome were more frequent at earlier gestational age than preeclampsia and HUS/TTP group. Comparison between study cases as regards ICU data shown in Tab. 17.

| Variables | PE-Eclampsia-HELLP | HUS/TTP | AFLP | Overlap syndrome | Test value | P-value | Sig. | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No.=568 | No.=12 | No.=12 | No.=8 | |||||

| Highest ICU PULSE | Mean ± SD | 96.82 ± 8.83 | 103.33 ± 4.92 | 97.50 ± 13.36 | 104.00 ± 17.10 | 3.685 | 0.012 | S |

| Range | 80–120 | 100–110 | 85–110 | 88–120 | ||||

| Highest ICU SBP | Mean ± SD | 177.83 ± 19.63 | 126.67 ± 4.92 | 140.00 ± 10.69 | 155.00 ± 48.11 | 37.679 | 0.000 | HS |

| Range | 110–220 | 120–130 | 130–150 | 110–200 | ||||

| Highest ICU DBP | Mean ± SD | 106.57 ± 12.97 | 80.00 ± 8.53 | 90.00 ± 10.69 | 90.00 ± 21.38 | 24.222 | 0.000 | HS |

| Range | 70–160 | 70–90 | 80–100 | 70–110 | ||||

| Highest ICU TEMP | Mean ± SD | 36.99 ± 0.33 | 37.53 ± 1.08 | 36.90 ± 0.11 | 36.90 ± 0.11 | 9.528 | 0.000 | HS |

| Range | 36.5–39 | 36.8–39 | 36.8–37 | 36.8–37 | ||||

| Lowest ICU UOP/hour | Mean ± SD | 60.28 ± 15.91 | 45.00 ± 7.39 | 50.00 ± 10.69 | 50.00 ± 0.00 | 5.841 | 0.001 | HS |

| Range | 40–110 | 40–55 | 40–60 | 50–50 | ||||

| ICU Glasgow base | Mean ± SD | 11.60 ± 1.47 | 5.33 ± 3.45 | 8.00 ± 1.07 | 7.00 ± 1.07 | 101.861 | 0.000 | HS |

| Range | 3–14 | 3–10 | 7–9 | 6–8 | ||||

| Glasgow Lowest | Mean ± SD | 11.22 ± 1.37 | 9.00 ± 0.00 | 7.50 ± 4.81 | 10.00 ± 1.07 | 27.816 | 0.000 | HS |

| Range | 7–14 | 9–9 | 3–12 | 9–11 | ||||

| Glasgow Discharge | Mean ± SD | 13.68 ± 1.65 | 6.67 ± 5.42 | 8.50 ± 5.88 | 8.50 ± 5.88 | 82.025 | 0.000 | HS |

| Range | 3–15 | 3–14 | 3–14 | 3–14 | ||||

Tab. 17. Comparison between study cases as regards ICU data.

This table show that that there was statistically significant difference found between 4 groups of diseases in present study regarding ICU data, elevated systolic and diastolic blood pressure was mostly prominent in PE-ECLAMPSIA-HELLP group more than other groups. GALASCOW coma scale base and at discharge was significant low in patients with AFLP than other groups. Urine output was lowest in patients with HUS and TTP.

Comparison between study cases as regard haemoglobin level & INR shown in Tab. 18. This table show that there was high statistically significant difference found between 4 groups of diseases in present study regarding haemoglobin level at time of admission and discharge, Hb was lowest in patient with TTP&HUS, also INR was highest in patients with overlap syndrome then AFLP. Comparison between HELLP, HUS and TTP regarding PLT level lowest and at discharge (Tab. 19.). This table shows that there was high statistically significant increase in the lowest PLT level in cases with HUS and TTP than those cases with HELLP and at discharge PLT level was lowest in HUS then in TTP highest in HELLP. with p-value=0.00. Tab. 20. shows that there was high statistically significant difference found between 4 groups of diseases in present study regarding kidney function tests, serum creatnine level was highest in patients with overlap syndrome and HUS at admission to ICU and also at discharge. The median of ALT at time of admission was statically highly significant higher in AFLP patients (p0.000) compared to HUS/TTP and Preeclampsia, eclampsia and HELLP group (Tab. 21.). Tab. 22. Shows that the median of ALT at time of admission was statically highly significant in cases with AFLP than those cases with SPET and even also at discharge, with p-value=0.00. Tab. 23. Shows that there was statistically significant difference found between 4 groups of diseases in present study regarding duration of ICU stay, it was more in patients with AFLP than other groups, also there was statistically significant difference regarding maternal outcome between 4 groups. The maternal death rate was highest in patients with HUS/TTP than other groups by 66% versus 2.1%, 33.3% and 50% for PE-Eclampsia –HELLP, AFLP and Overlap syndrome respectively. Highest recovery was in patients with PE-ECLAMPSIA-HELLP.

| Variables | PE-Eclampsia-HELLP | HUS/TTP | AFLP | Overlap syndrome | Test value | P-value | Sig. | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No.=568 | No.=12 | No.=12 | No.=8 | |||||

| Lowest Hb | Mean ± SD | 9.10 ± 0.91 | 7.63 ± 1.03 | 11.00 ± 0.00 | 8.10 ± 1.18 | 24.867 | 0.000 | HS |

| Range | 6.5–11 | 6.5–8.9 | 11–11 | 7–9.2 | ||||

| Hb at discharge | Mean±SD | 10.06 ± 0.80 | 7.33 ± 1.89 | 9.75 ± 1.06 | 7.90 ± 2.69 | 14.081 | 0.000 | HS |

| Range | 6–11.9 | 6–9.5 | 9–10.5 | 6–9.8 | ||||

| Clotting INR | Mean ± SD | 0.99 ± 0.11 | 1.07 ± 0.10 | 1.25 ± 0.05 | 2.24 ± 0.00 | 205.907 | 0.000 | HS |

| Range | 0.7–1.4 | 1–1.2 | 1.2–1.3 | 2.24–2.24 | ||||

Tab. 18. Comparison between study cases as regard haemoglobin level & INR.

| Variables | HELLP | HUS | TTP | Test value | P-value | Sig. | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No.=100 | No.=8 | No.=4 | |||||

| PLT | Mean ± SD | 99.88 ± 34.80 | 147.00 ± 93.01 | 90.00 ± 0.00 | 5.176 | 0.007 | HS |

| Range | 47–210 | 60–234 | 90–90 | ||||

| PLT at discharge | Mean ± SD | 165.52 ± 29.13 | 92.50 ± 40.09 | 180.00 ± 0.00 | 23.463 | 0.000 | HS |

| Range | 55–230 | 55–130 | 180–180 | ||||

Tab. 19. Comparison between HELLP, HUS and TTP regarding PLT level lowest and at discharge.

| Variables | PE-Eclampsia-HELLP | HUS/TTP | AFLP | Overlap syndrome | Test value | P-value | Sig. | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No.=568 | No.=12 | No.=12 | No.=8 | |||||

| Urinary albumin | ALB nil | 8 (1.4%) | 0 (0.0%) | 8 (66.6%) | 4 (50.0%) | 150.232 | 0.000 | HS |

| ALB + | 64 (11.3%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | ||||

| ALB ++ | 256 (45.1%) | 4 (33.3%) | 4 (33.3%) | 4 (50.0%) | ||||

| ALB +++ | 224 (39.4%) | 8 (66.7%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | ||||

| ALB trace | 16 (2.8%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | ||||

| Urea | Median (IQR) | 40 (31-50) | 135 (130-300) | 41.5 (33-50) | 50 (50-50) | 37.858 | 0.000 | HS |

| Range | 14–300 | 130–300 | 33–50 | 50–50 | ||||

| Serum creatnine | Median (IQR) | 0.9 (0.8-1) | 2 (1.5-2.3 | 1.8 (1.3-2.3) | 2.35 (0.8 -3.9) | 50.817 | 0.000 | HS |

| Range | 0.5–103 | 1.5–2.3 | 1.3–2.3 | 0.8–3.9 | ||||

| Serum creatnine at discharge ** | Median (IQR) | 0.9 (0.9–1) | 5 (4.2–5.5) | 2.25 (1–3.5) | 5.15 (4.8–5.5) | 73.460 | 0.000 | HS |

| Range | 0.6–8 | 4.2–5.5 | 1–3.5 | 4.8–5.5 | ||||

*:Chi-square test; •: One Way ANOVA test; ‡: Kruskal Wallis test

** discharge refers to improvement or death or renal failure.

Tab. 20. Shows comparison between study cases as regard kidney function tests.

| Variables | PE-Eclampsia-HELLP | HUS/TTP | AFLP | Overlap syndrome | Test value | P-value | Sig. | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No.=568 | No.=12 | No.=12 | No.=8 | |||||

| ALT | Median (IQR) | 40 (22-81) | 60 (50-340) | 154.5 (119-190) | 87.5 (58-117) | 20.731 | 0.000 | HS |

| Range | 9–340 | 50–340 | 119–190 | 58–117 | ||||

| ALT at discharge | Median (IQR) | 25 (20–34) | 400 (30–410) | 116 (32–200) | 126.5 (40–213) | 12.384 | 0.006 | HS |

| Range | 11–323 | 30–410 | 32–200 | 40–213 | ||||

| AST | Median (IQR) | 27 (16-80) | 65 (44-400) | 200 (175-225) | 207.5 (31-384) | 24.541 | 0.000 | HS |

| Range | 7–410 | 44–400 | 175–225 | 31–384 | ||||

| AST at discharge | Median (IQR) | 26 (19–33) | 420 (25–433) | 126.5 (36–217) | 194.5 (33–356) | 11.434 | 0.010 | S |

| Range | 7–354 | 25–433 | 36–217 | 33-356 | ||||

| LDH | Median (IQR) | 350 (211-600) | 2951 (634-5268) | 621 (542-700) | 600 (600-600) | 19.743 | 0.000 | HS |

| Range | 180–943 | 634–5268 | 542–700 | 600–600 | ||||

*:Chi-square test; •: One Way ANOVA test; ‡: Kruskal Wallis test

Tab. 21. Comparison between study cases as regard liver function tests.

| Variables | SPET | AFLP | Test value | P-value | Sig. | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No.=456 | No.=12 | |||||

| ALT | Median (IQR) | 30 (19–60) | 190 (119–190) | -5.056 | 0.000 | HS |

| Range | 9–340 | 119–190 | ||||

| AST | Median (IQR) | 21 (15–63) | 175 (175–225) | -5.126 | 0.000 | HS |

| Range | 7–410 | 175–225 | ||||

| ALT at discharge | Median (IQR) | 25 (19–32) | 41 (32–200) | -4.814 | 0.000 | HS |

| Range | 11–154 | 32–200 | ||||

| AST at discharge | Median (IQR) | 25 (19–32) | 36 (32–217) | -4.557 | 0.000 | HS |

| Range | 7–123 | 32–217 | ||||

*:Chi-square test; ‡: Kruskal Wallis test

Tab. 22. Comparison between SPET and AFLP regarding liver enzymes.

| Variables | PE-Eclampsia-HELLP | HUS/TTP | AFLP | Overlap syndrome | Test value | P-value | Sig. | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No.=568 | No.=12 | No.=12 | No.=8 | |||||

| Duration of ICU (day) |

Median(IQR) | 2 (1-2) | 3 (2-9) | 9 (1-17) | 2 (1-3) | 14.048‡ | 0.003 | HS |

| Range | 0–17 | 2–9 | 1–17 | 1–3 | ||||

| Outcome | Death | 12 (2.1%) | 8 (66.6%) | 4 (33.3%) | 4 (50.0%) | 186.078* | 0.000 | HS |

| Recovery | 556 (97.8%) | 4 (33.3%) | 8 (66.6%) | 4 (50.0%) | ||||

*:Chi-square test; ‡: Kruskal Wallis test

Tab. 23. Shows comparison between study cases regarding duration of ICU stay and maternal outcome.

Maternal death occurred in 28 cases (4.7%), 8 (7.2%) of them were HELLP syndrome, 4 cases (0.6%) were HUS, 4 cases (0.6%) were undiagnosed cases, 4 cases (0.6%) were AFLP, 4 cases were SPET, 4 cases were Eclampsia. The main causes of death were multi-organ dysfunction, pulmonary emboli, DIC, Cerebral haemorrhage and stroke. Regarding the case fatality rate it was 8% for HELLP, 50% for HUS, 100% for undiagnosed cases & 33% for AFLP.

Poor outcome represented in death, renal failure and the occurrence of fits. Tab. 24. shows that there was statistically significant difference in blood pressure regarding the 3 groups with increase in systolic and diastolic blood pressure in cases with eclamptic fits than renal failure cases and maternal deathes with p-value 0.002 and < 0.01 in systolic and diastolic groups respectively.

| Variables | Outcome | Test value• | P-value | Sig. | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Death | Renal failure | Fits | |||||

| No.=24 | No.=8 | No.=12 | |||||

| ICU systolic blood pressure |

Mean ± SD | 150.00 ± 36.83 | 115.00 ± 5.35 | 163.33 ± 9.85 | 7.328 | 0.002 | HS |

| Range | 110–200 | 110–120 | 150–170 | ||||

| ICU diastolic Blood pressure |

Mean ± SD | 90.00 ± 15.60 | 70.00 ± 0.00 | 106.67 ± 4.92 | 22.702 | 0.000 | HS |

| Range | 70–110 | 70–70 | 100–110 | ||||

| ICU Glasgow BASE |

Mean ± SD | 6.00 ± 2.36 | 8.00 ± 2.14 | 7.67 ± 0.98 | 4.310 | 0.020 | S |

| Range | 3–9 | 6–10 | 7–9 | ||||

| Glasgow LOWEST |

Mean ± SD | 8.17 ± 2.53 | 10.00 ± 1.07 | 8.67 ± 2.46 | 1.864 | 0.168 | NS |

| Range | 3–11 | 9–11 | 7–12 | ||||

| Glasgow discharge | Mean ± SD | 4.83 ± 4.19 | 14.00 ± 0.00 | 9.67 ± 4.92 | 17.151 | 0.000 | HS |

| Range | 3–5 | 14–14 | 3–13 | ||||

*: One Way ANOVA test

Tab. 24. Shows correlation between clinical data and poor outcome.

Also there was statistically significant difference between three poor outcomes regarding Glasgow coma scale at time of discharge, ICU Glasgow scale at admission was high in cases with eclamptic fits than renal failure patients or whose died with p-value 0.020 while the lowest Glasgow scale level was greater in maternal death than renal failure and eclamptic fits mothers with p-value 0.168, while the highest glascow coma scale at discharge was in renal failure patients than the other groups with p-value <0.01.

High blood pressure is indicator to developing eclampsia and low galscow coma scale at admission indicate poor prognosis and death. There was statistically significant difference between three poor outcomes regarding creatinine, ALT&AST at discharge, creatinine was highest in patients with renal failure, ALT & AST were highest in patients died. Low Hb level, elevated liver enzymes and elevated serum creatnine indicate poor prognosis and death (Tab. 25.).

| Variables | Outcome | Test value | P-value | Sig. | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Death | Renal failure | Fits | |||||

| No.=24 | No.=8 | No.=12 | |||||

| Hb | Mean ± SD | 8.53 ± 1.68 | 9.05 ± 0.16 | 10.00 ± 0.74 | 4.962• | 0.012 | S |

| Range | 6.5–11 | 8.9–9.2 | 9.5–11 | ||||

| PLT | Mean ± SD | 151.00 ± 92.15 | 185.50 ± 102.09 | 123.33 ± 4.92 | 1.423• | 0.253 | NS |

| Range | 55–281 | 90–281 | 120–130 | ||||

| Creat at discharge | Median(IQR) | 3.85(3.2-5) | 5.15(4.8-5.5) | 1(0.9-2.5) | 29.125‡ | 0.000 | HS |

| Range | 2.9–5.5 | 4.8–5.5 | 0.9–2.5 | ||||

| ALT at discharge | Median(IQR) | 268(200-400) | 35(30-40) | 43(37-250) | 23.976‡ | 0.000 | HS |

| Range | 154–410 | 30–40 | 37–250 | ||||

| AST at discharge | Median(IQR) | 355(217-420) | 29(25-33) | 35(26-234) | 26.777‡ | 0.000 | HS |

| Range | 123–433 | 25–33 | 26–234 | ||||

*: One Way ANOVA test; ‡: Kruskal Wallis test

Tab. 25. Showing correlation between laboratory finding and poor outcome.

Discussion

Microangiopathic hemolytic anemia (MAHA) is used to designate any hemolytic anemia related to RBC fragmentation, occurring in association with small vessel disease. The term “thrombotic microangiopathy (TMA)” is also used to describe syndromes characterized by MAHA, thrombocytopenia, and thrombotic lesions in small blood vessels [5].

Most females complete their pregnancy with no complications, yet a few of them develop unexpected events due to pregnancy and require ICU care [6]. There are several studies discussing indications for admission, interventions and outcome of critically ill obstetric patients admitted in the intensive care unit, but there are few studies discuss criteria of patients admitted to obstetric ICU for MAHA variants.

In present study; the most common reasons for ICU admission were preeclampsia and HELLP (92.7%), followed by Eclampsia (2%) and AFLP (2%), then HUS (1.3%), TTP (0.7%), whereas overlap syndrome &cases which we could not reach a final diagnosis represented (1.4)%.

The mean maternal age for patients admitted with HELLP syndrome in the study was 30.22 ± 6.24 years at the time of presentation which was in agreement with what Cappell reported in his study [7]. The mean age of our patients with TTP at time of presentation was 25.67 ± 4.70 years and that was in contrast to the same author who reported a mean age of 40 years at time of presentation. AFLP presents more frequent in older age females while TTP/HUS were more in younger age females. The mean distribution of age in the patients of the current study was 30.22 ± 6.24 years, while in the study conducted by Ashraf N, et al. [8] this was 26.34 ± 5.34years, and in that of Lin this was 31 years [9]. This variation might be due to differences in cultures that effect age of marriage.

Regarding the past obstetric history of present study population, the mean parity was 3.3 ± 1.16. In our cases, AFLP has higher incidence among primigravidas more than multiparas woman, 60% were primigravida, while overlap syndrome and undiagnosed MAHA was higher among multiparous women all 8 cases with overlap syndrome and undiagnosed MAHA were multiparas. Also, TTP HUS was higher among primigravidas than multiparous (8 cases were primigravidas, while 4 cases were multiparous).

Most of the patients in present study were admitted at post-partum period. However, in the study of Ashraf N, et al. [8]; the majority of their patients were admitted during the antepartum period. On the other hand, most of the authors reported a higher incidence of postpartum admission [8,9]. This might be related to hemodynamic changes in the postpartum period, including plasma oncotic pressure changes, increase in cardiac output and acute blood loss during delivery that might precipitate MAHA complications [10,11].

The average length of ICU stays in our cases was 2.8 ± 1.64 days which was comparable to other studies such as [12,13]. Patients with AFLP had the highest duration of stay in the ICU among all other variants of MAHA (median was 9 days – range from one day to 17 days), while preeclampsia- eclampsia and HELLP syndrome have the lowest duration of ICU stay (median 2 days).

This reported incidence of IUGR in present study is lower than that reported by other studies, who reported incidence of IUGR was 27.5% among patients with preeclampsia –eclampsia and HELLP syndrome and Chandil N, et al. [14]. In present study we also found that 28 cases (33.7%) were complicated by pre-term labor. this was lower than that reported by Haram K, et al. [15] who reported that incidence of preterm labour was 65% for HELLP syndrome patients, with a mean gestation at delivery of 33.5 weeks. Also, Egerman RS, et al. [16] reported an incidence of pre-term labor 62.5% for TTP patients.

Present study showed that maternal death occurred in 28 cases (4.7%), 8 (1.3%) of them were HELLP syndrome, 4 cases (0.6%) were HUS, 4 cases (0.6%) were undiagnosed cases, 4 cases (0.6%) were AFLP. However, when the case fatality rates were calculated it was 8% for HELLP, 50% for HUS, 100% for undiagnosed cases & 33% for AFLP. This was comparable to Vigil-de Gracia P, et al. [17] who reported that mortality rate in AFLP was 11.4% and was in agreement with that reported by Noris M and Remuzzi G [18] who reported maternal mortality related to HUS was 50-60%.

In another retrospective cohort study comprising 442 pregnancies complicated by the HELLP syndrome, the overall maternal mortality was 1.1% [19]. However, higher maternal mortality (up to 25%) has been reported by Aslan H, et al. [20]. The main causes of death were multi-organ dysfunction, pulmonary emboli, DIC and cerebral hemorrhage.

Regarding risk factors among study population smoking was found not to be a risk factor for any of the diseases included in the study. This was in agreement with Mostello D, et al. [21] who reported that Smoking was protective from devolving preeclampsia.

In present study renal failure occurred in 8 cases 4 of them was HUS patients. In a case series of 442 women with HELLP syndrome, Sibai BM, et al. [19] reported that 33 (7%) had acute renal failure, defined by creatinine clearance <20 ml/min. However, an earlier report from these authors described acute renal failure in only three of 303 (1%) patients; all three were associated with abruptio placentae and DIC; all recovered normal renal function [19].

Regarding thrombocytopenia and microangiopathic hemolytic anemia, in present study thrombocytopenia was more in TTP, HELLP then in HUS. In another study [22] in which half of women with preeclampsia were thrombocytopenic, half of the thrombocytopenic women had platelet counts <100,000 µL.

Regarding the management of those cases, we found that termination of pregnancy after trial of correction of maternal general condition was done, 556 cases (92.7%) ended by caesarian section and the remaining 24 cases (4.0%) ended by successful vaginal delivery. CS hysterectomy was done in 0.7% of the cases, D&C and suction evacuation were done in 2% of the cases.

This was comparable to Murphy DJ and Stirrat GM [23] who reported incidence of ceaseran section in patients with preeclampsia eclampsia and help syndrome was 80%. Also Zhang Y, et al. [24] who reported incidence of ceaseran section in patients with preeclampsia, eclampsia and HELLP syndrome was 88.258%. In another retrospective study for acute fatty liver in pregnancy Dwivedi S and Runmei M [25] reported 109 (86.5%) pregnancies were terminated by cesarean section and of those cases 14 patients died. Seventeen (13.4%) patients delivered vaginally resulting in 6 deaths. The mortality rate of the mothers who underwent cesarean section (12.8%) was lower than those who delivered vaginally (35.2%).

Strengths and Weaknesses of the Study

Strengths: The study highlights a clinically challenging, yet rare, situation of a thrombotic microangiopathy in pregnancy. The large number of files recruited (600 files), and the long duration covered (5 years) are points of strength in this study. Additionally the study examined a wide spectrum of different demographic, clinical and laboratory parameters against the development of each type of MAHA and also their correlation to maternal and neonatal morbidity and mortality.

Weakness: Given the retrospective nature of our study, we were unable to trace the long term outcomes of different diseases in the study. Besides, correlations between the risk factors and negative fetal/infant outcomes could not be sufficiently explained. Insufficient data and poor registration were found in some files. Finally the data recruited represent only the magnitude of the problem in our hospital (A tertiary referral centre) which cannot be generalized to the magnitude of the problem in the general obstetric population.

Conclusion

Present study concluded that these are acute conditions with significant morbidity and mortality. Certain demographic, clinical and laboratory characteristics could correlate to specific types of MAHA. Additionally, such factors can be used as predictors of prognosis in different MAHA variants. Early diagnosis and termination of pregnancy can result in marked reduction of maternal mortality in such cases.

References

- Moake JL. Thrombotic microangiopathies. N Engl J Med. 2002;347(8):589-600.

- George JN, Nester CM. Syndromes of thrombotic microangiopathy. N Engl J Med. 2014;371(7):654-666.

- Scully M, Hunt BJ, Benjamin S, et al. Guidelines on the diagnosis and management of thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura and other thrombotic microangiopathies. Br J Haematol. 2012;158(3):323-335.

- Taylor CM, Machin S, Wigmore SJ, et al. Clinical practice guidelines for the management of atypical haemolytic uraemic syndrome in the United Kingdom. Br J Haematol. 2010;148(1):37-47.

- Morishita E. Diagnosis and treatment of microangiopathic hemolytic anemia. Japanese J Clin Hematol. 2015;56(7):795-806.

- Bhat PB, Navada MH, Rao SV, et al. Evaluation of obstetric admissions to intensive care unit of a tertiary referral center in coastal India. Indian J Crit Care Med. 2013;17(1):34.

- Reuter-Lorenz PA, Cappell KA. Neurocognitive aging and the compensation hypothesis. Curr Dir Psychol Sci. 2008;17(3):177-182.

- Ashraf N, Mishra SK, Kundra P, et al. Obstetric patients requiring intensive care: A one year retrospective study in a tertiary care institute in India. Anesthesiol Res Pract. 2014;2014.

- Cohen J, Singer P, Kogan A, et al. Course and outcome of obstetric patients in a general intensive care unit. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2000;79(10):846-850.

- Afessa B, Green B, Delke I, et al. Systemic inflammatory response syndrome, organ failure, and outcome in critically ill obstetric patients treated in an ICU. Chest. 2001;120(4):1271-1277.

- Aldawood A. Clinical characteristics and outcomes of critically ill obstetric patients: A ten-year review. Ann Saudi Med. 2011;31(5):518-522.

- Lin Y, Zhu X, Liu F, et al. Analysis of risk factors of prolonged intensive care unit stay of critically ill obstetric patients: A 5-year retrospective review in 3 hospitals in Beijing. Crit Care Med. 2011;23(8):449-453.

- Rios FG, Risso-Vázquez A, Alvarez J, et al. Clinical characteristics and outcomes of obstetric patients admitted to the intensive care unit. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2012;119(2):136-140.

- Chandil N, Luthra S, Dwivedi AD, et al. Prevalence of thrombocytopenia during pregnancy, and its effect on pregnancy and perinatal outcome. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2020;4(2):60-62.

- Haram K, Svendsen E, Abildgaard U. The HELLP syndrome: Clinical issues and management. A Review. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2009;9(1):1-5.

- Egerman RS, Witlin AG, Friedman SA, et al. Thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura and hemolytic uremic syndrome in pregnancy: Review of 11 cases. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1996;175(4):950-956.

- Vigil-de Gracia P, Montufar-Rueda C. Acute fatty liver of pregnancy: Diagnosis, treatment, and outcome based on 35 consecutive cases. J Matern.-Fetal Neonatal Med. 2011;24(9):1143-1146.

- Noris M, Remuzzi G. Hemolytic uremic syndrome. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2005;16(4):1035-1050.

- Sibai BM, Ramadan MK, Usta I, et al. Maternal morbidity and mortality in 442 pregnancies with hemolysis, elevated liver enzymes, and low platelets (HELLP syndrome). Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1993;169(4):1000-1006.

- Aslan H, Gul A, Cebeci A. Neonatal outcome in pregnancies after preterm delivery for HELLP syndrome. Gynecol Obstet Invest. 2004;58(2):96-99.

- Mostello D, Catlin TK, Roman L, et al. Preeclampsia in the parous woman: Who is at risk?. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2002;187(2):425-429.

- Katz VL, Thorp JM, Rozas L, et al. The natural history of thrombocytopenia associated with preeclampsia. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1990;163(4):1142-1143.

- Murphy DJ, Stirrat GM. Mortality and morbidity associated with early-onset preeclampsia. Hypertens Pregnancy. 2000;19(2):221-231.

- Zhang Y, Li W, Xiao J, et al. The complication and mode of delivery in Chinese women with severe preeclampsia: a retrospective study. Hypertens Pregnancy. 2014;33(3):283-290.

- Dwivedi S, Runmei M. Retrospective study of seven cases with acute fatty liver of pregnancy. Int Sch Res Notices. 2013;2013.

Google Scholar, Crossref, Indexed at

Google Scholar, Crossref, Indexed at

Google Scholar, Crossref, Indexed at

Google Scholar, Crossref, Indexed at

Google Scholar, Crossref, Indexed at

Google Scholar, Crossref, Indexed at

Google Scholar, Crossref, Indexed at

Google Scholar, Crossref, Indexed at

Google Scholar, Crossref, Indexed at

Google Scholar, Crossref, Indexed at

Google Scholar, Crossref, Indexed at

Google Scholar, Crossref, Indexed at

Google Scholar, Crossref, Indexed at

Google Scholar, Crossref, Indexed at

Google Scholar, Crossref, Indexed at

Google Scholar, Crossref, Indexed at

Google Scholar, Crossref, Indexed at

Google Scholar, Crossref, Indexed at

Author Info

Heba Abd El KarimCopyright:This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.